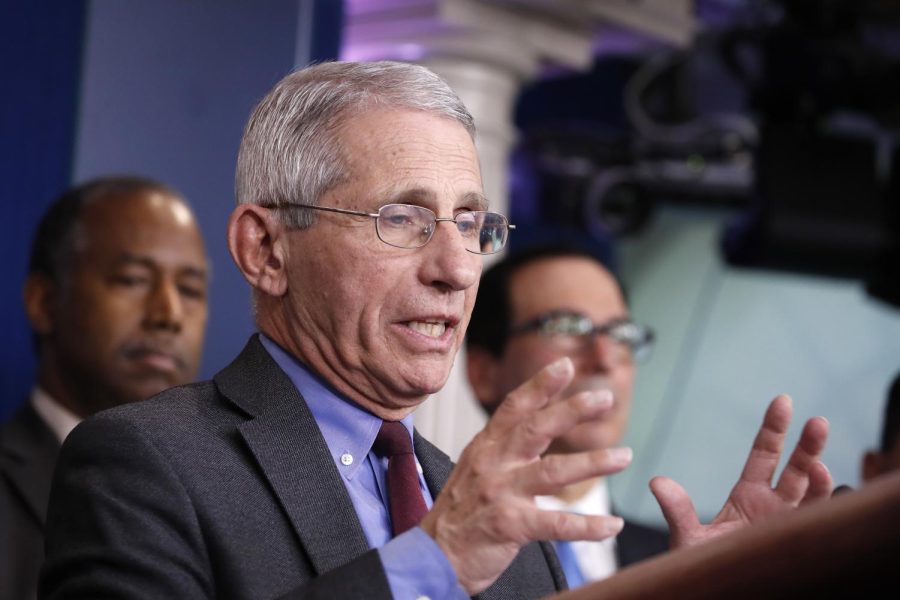

Straight-talking Fauci explains outbreak to a worried nation

The fear and confusion of outbreaks aren’t new to Fauci, who in more than 30 years has handled HIV, SARS, MERS, Ebola and even the nation’s 2001 experience with bioterrorism — the anthrax attacks.

Fauci’s political bosses — from Ronald Reagan to Donald Trump — have let him do the explaining because he’s frank and understandable, translating complex medical information into everyday language while neither exaggerating nor downplaying.

If you quizzed former presidents about who influenced their views on infectious diseases, “Tony’s name would be first on the list, and you wouldn’t have to remind them,” said former health secretary Mike Leavitt, who worked with Fauci on bird flu preparedness.

At 79, the government’s top infectious disease expert is by age in the demographic group at high risk for COVID-19. But he’s working round the clock and getting only a few hours of sleep. He’s a little hoarse from all the talking about coronavirus, and he’ll be on the TV news shows Sunday. Yet his vigor belies his age, and he credits it to exercise, including running. As of Thursday, he had not been tested for coronavirus. The National Institutes of Health, where he works, said that’s because he hasn’t needed to be.

Fauci uses a metaphor from one of the fastest-moving sports to describe his strategy on the outbreak. “You skate not to where the puck is, but to where the puck is going to be,” he told a House committee.

So he’s simultaneously advocating containment to try to keep the virus from spreading, mitigation to check its damage once it gets loose in a community, immediate efforts to increase testing, and short-term and long-term science to develop treatments and vaccines. He’s hoping a dynamic response will put the nation where the puck ends up going.

“It’s unpredictable,” he said. “Testing now is not going to tell you how many cases you’re going to have. What will tell you … will be how you respond to it with containment and mitigation.”

Serving a president who until recently dismissed coronavirus by comparing it to seasonal flu, Fauci has been even-handed in public. He’s won the respect of Democratic and Republican lawmakers, along with Trump administration officials.

Almost in matter-of-fact fashion Fauci acknowledged to Congress in recent days that the government system wasn’t designed for mass testing of potential infections. “It is a failing, let’s admit it,” he told lawmakers.

But he also supported President Donald Trump’s restrictions on travel from Europe. It’s part of the containment strategy, he explained. “It was pretty compelling that we needed to turn off the source from that region,” he said.

The threat of a pandemic has been on Fauci’s mind for years. Many scientists thought it would come from the flu, but it turned out to be coronavirus.

Fauci was unflappable answering questions for hours from the House Oversight and Reform committee last week __ except if there was any hint of questioning his scientific integrity.

“I served six presidents and I have never done anything other than tell the exact scientific evidence and made policy recommendations based on the science and the evidence,” he said.

Democrats and Republicans have welcomed his approach.

“The scientists I’ve spoken with in committee see you as the lead man, and I believe most of America does,” Rep. Clay Higgins, R-La., told Fauci.

Democratic Rep. Stephen Lynch of Massachusetts praised Fauci for accurately stating that a vaccine would not be available in a matter of months, contrary to what Trump has suggested at times.

“You have a certain level of credibility and honesty that I think … should be persuasive to the American people,” Lynch told him.

Fauci’s candor hasn’t stopped Trump from praising him. “Tony has been doing a tremendous job working long, long hours,” the president said Friday at a Rose Garden event.

Anthony Stephen Fauci was born in Brooklyn, New York, on Christmas Eve, 1940, into an Italian-American family. President George W. Bush, who in 2008 awarded Fauci the Presidential Medal of Freedom, noted that even as a boy he showed an independent streak: In a neighborhood full of Brooklyn Dodgers fans, Fauci rooted for the Yankees.

Fauci became head of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases in 1984, when the nation was in the throes of the AIDS crisis. He’s recalled the huge frustration of caring for dying patients in the NIH’s hospital with nothing to offer.

After hours, he’d chat with then-Surgeon General C. Everett Koop about what scientists were learning about AIDS, influencing Koop’s famous 1986 report educating Americans about the disease.

In 1990, when AIDS activists swarmed the NIH to protest what they saw as government indifference, Fauci brought them to the table. Fast forward, and he helped to shape Trump’s initiative to end HIV in the U.S.

Although he’s spent his career in government, Fauci doesn’t seem to have lost the human touch — and that may be part of the key to his success as a communicator.

During the 2014 Ebola outbreak, many Americans panicked when a U.S. nurse got infected by a patient she was caring for, a traveler from West Africa. Ebola can cause deadly bleeding.

Fauci confronted those fears by setting a personal example. When the NIH hospital released that nurse, not only did he say she wasn’t contagious, he gave her a hug before TV cameras to prove he was not worried.