Projections show Ohio likely to lose House seats following 2020 Census

Editor’s note: This story is the work of Kent State’s School of Journalism and Mass Communication’s Interviewing and Data class.

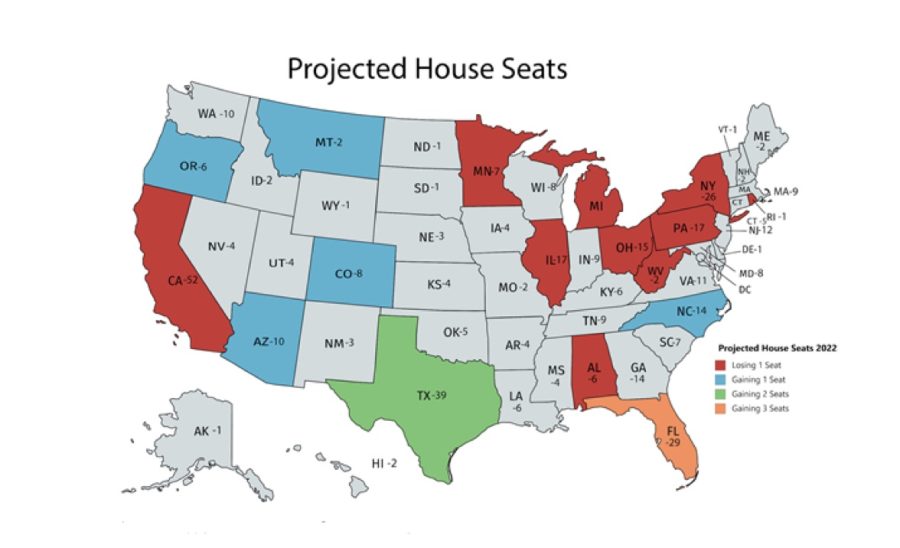

Ohio is one of 10 states — mainly across the Rust Belt — likely to lose seats in the House of Representatives following the 2020 Census.

Projections by Kent State’s Interviewing and Data class show one of the Buckeye State’s 16 congressional districts will be eliminated when the 435 House seats are divided up to reflect the new state population counts. As a result, Ohio will lose federal dollars and political power, say politicians and public policy experts.

“If you lose representation in Congress, you have less people there to advocate for programs of importance,” said Wendy Patton, an expert on state funding from the nonprofit Policy Matters Ohio.

Patton said those federal funds are used to pay for the state’s highways, education, domestic violence shelters and health care programs.

House seats are assigned through a process formally called “reapportionment,” based on state populations reported by the Census Bureau no later than a year after the April 1 census.

Each state automatically gets one district. The remaining 385 seats will be assigned, and new district lines drawn with the goal of having each district contain roughly the same number of people.

While the math of reapportionment is complex, the bottom line is easy to understand: more populous states get more seats and less populous states get fewer seats.

Projections of student reporters in Kent State’s Interviewing and Data class, which are based on Census Bureau’s annual population estimates, show the big winners will be Texas, which stands to gain three seats, and Florida, which would gain two. Other Sun Belt and Western states gaining more districts include Arizona, Colorado, Montana, North Carolina and Oregon.

In addition to Ohio, seven other states in the Northeast would lose seats: Illinois, Michigan, Minnesota, New York, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island and West Virginia.

Only one Southern state, Alabama, and one Western state, California, are expected to lose districts.

The movement of people out of the northeast is a near-century-long trend.

“I think it’s really a continuation of what we’ve seen since 1930,” Kimball Brace, the president of Election Data Services Inc., told Politico in December. “It is a movement away from the Northeast and the Upper Midwest to the South and to the West.”

This is not the first time Ohio, traditionally a powerful swing state on the national political scene, has seen its congressional delegation shrink. The state lost at least one seat following each of the last five censuses since 1960, when it peaked at 24.

It is not that Ohio is shrinking in population; it just is not growing as fast as many other states.

Since 2010, Ohio’s populations increased by about 1.3 percent to an estimated 11.7 million last year, according to the Census Bureau. Over those same nine years, Texas’s population shot up by more than 15 percent — nearly 12 times faster.

The reapportionment process does not end when all the House seats are assigned. The states still must redraw all House districts in preparation for the 2022 elections.

For members in states that lose seats, redistricting will be a political version of musical chairs.

How the class calculated the number of House seats

The mathematics used to determine how many House seats Ohio and the other states will get following the 2020 census is complex. But the methodology used by Kent State’s Interviewing and Data class to project the underlying population counts is simple and straightforward.

1. Using the latest U.S. Census Bureau population estimates, we calculated average rates of population change from 2010 and 2019 for all 50 states. We then used those numbers to calculate projected populations for this year, when the new census will be done April.

2. Because of members of the armed forces, diplomats and other federal employees living abroad, we included in the reapportionment calculation rough estimates of overseas residents for each state.

3. Final population projections were copied and pasted into an apportionment calculator, created by the University of Michigan’s Population Studies Center, to compute how many House seats each state would get.

How accurate are our projections?

We will not know for sure until the 2020 census counts are released next year.

Asked to comment on our methodology, EDS President Kimball Brace said, “I think it’s pretty good; it is very similar to what we did.”

Jeffrey Howison, chief demographer for Ohio State’s Office of Research Development Services Agency, agreed, saying the way we did the projections “is legit.”

“I wouldn’t have any problem with that or trying to defend that methodology,” Howison said.

“The first two years of any decade when districts are drawn produce the whitest knuckles in Congress,” former Rep. Steve Israel, D-N.Y., told Politico in December. “People are trying to hold onto their seats at all costs.”

Ohio’s redistricting will be watched especially closely to determine the effectiveness of Issue 1, a ballot initiative overwhelmingly approved by voters in 2018 that aims to curb gerrymandering, the practice of drawing convoluted district lines to benefit one political party.

Critics say Ohio is one of the most gerrymandered states in the nation. They blame Republican lawmakers’ exclusive control of redistricting following the 2010 census as a big reason for the lopsided results of Ohio’s congressional elections. In 2018, for example, GOP House candidates garnered little more than half the total votes but won 12 — three-quarters — of the state’s 16 districts.

Supporters of Issue 1 cited Summit County as an example of how gerrymandering works.

With a population of more than a half-million, the traditionally Democratic county has enough voters to dominate a congressional district. But the maps drawn by Republican lawmakers divided Summit County among four House districts — “packing” many of Akron’s voters into districts mainly representing Cleveland and Youngstown and “cracking” the county’s other voters into the more suburban and rural 14th and 16th districts, where Republicans are the majority.

As a result, “none of the four members of Congress who represent Summit County lives in the county,” noted a 2017 WKSU series, Gerrymandering: Shading the Lines.

“When you see gerrymandering in Ohio, there is a lot,” Aaron Godfrey, the Democrat challenging incumbent Republican Anthony Gonzalez in the 16th District said. “It robs everyone — Republican and Democrat — of being represented fairly.”

Ohio’s expected loss of a House seat will raise the stakes in the redistricting process, but not everyone agrees that will happen.

“We don’t know if we will be losing a seat yet or not,” Ohio Republican Party Communications Director Evan Machan said. “We won’t know until after the census.”

Ohio could keep all 16 districts if next month’s census finds about 120,000 more people than projected.

How likely is it that the estimates are that wrong?

To investigate that possibility, Kent State’s Interviewing and Data class used the 2000-to-2009 estimates to project a 2010 population for Ohio and compared that number to the 2010 census. The result: the bureau overestimated the actual census count by about 16,000 residents — about 0.1 percent.

Saving Ohio’s seat would require an error rate nearly 10 times bigger.

Jeffrey Howison, demographer for Ohio State’s Office of Research Development Services Agency, agreed that the Census Bureau has a good record for accuracy.

“By all reports that I’ve seen I think Ohio will most likely lose a seat in 2020,” he said.

John Berney, Dante Centofanti, Sophie Giffin, Kendra Hughley, Mason Lawlor, Zachary McKnight, Melissa Meyers, Cameron Miller, James Oswald, Benjamin Pagani, Michael Reed, Shelby Reeves, Maria Serra and Madisyn Woodring contributed to this report.