When the illness is invisible: Kent State students living with chronic illness turn to each other for support

Last spring, when a flare-up of arthritis symptoms landed Katie Murphy in the hospital the week before finals, she did what she’s always done in that situation: opened her laptop and got to work on assignments from her hospital bed.

Murphy is a senior special education major at Kent State who lives with juvenile idiopathic arthritis, an incurable disease that causes chronic inflammation of the joints in her back, hands, knees and feet. For her, arthritis manifests differently day to day — sometimes as debilitating, nausea-inducing pain that makes walking difficult, and sometimes as a duller pain that she can push through to focus on classes. But it’s always there.

“Some days, I’m fine, and other days, it’s so bad I can’t focus on anything else,” Murphy said. “It’s such a range. But there’s never a day I wake up and I’m not in pain.”

For any college student, times of high stress are inevitable, but for students living with chronic pain whose symptoms are exacerbated by stress, writing a paper while receiving fluids or steroids through an IV is a reality.

“I wish some professors could see how dedicated people with disabilities are,” Murphy said. “Even when they’re gone, they’re still working their hardest to keep up.”

To look at Murphy, you would never know she lives with arthritis. She is warm, composed and easy to talk to. She wears a Frida Kahlo pin on the collar of her jean jacket in homage to the artist whose honest and vivid self-portraits about living with disability resonate with her. Murphy speaks excitedly about her someday classroom, where she imagines herself connecting with and supporting students living with disabilities. She also speaks with a matter-of-factness about her pain and an acceptance of its permanence in her life, having lived with it since childhood.

Like Murphy, many Kent State students live with a chronic illness that is invisible to their professors and classmates. While Murphy has actively worked with Kent State’s Student Accessibility Services (SAS) office to discuss the assistance she needs to be academically successful, not all students living with chronic pain are well-supported. Those who are unable to access content or complete assignments with the help of accommodations often find themselves turning to each other for support, or dropping out.

A backlog of students

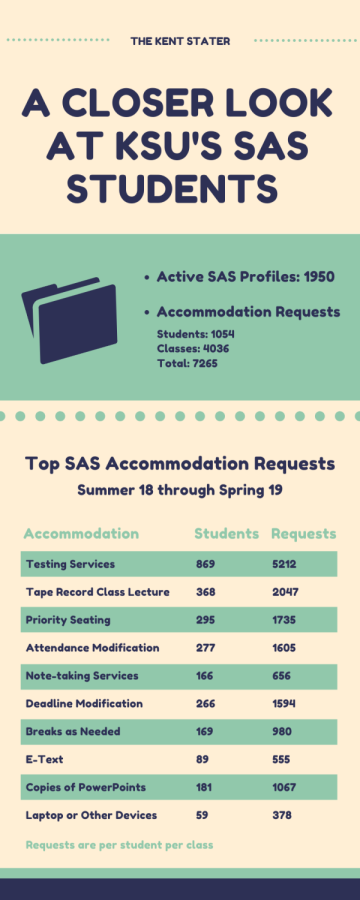

At Kent State, the number of students with disabilities seeking academic support has grown from about 1,100 to 1,500 over the past three years, said SAS Director Amanda Feaster.

One of the challenges for SAS this year has been the influx of referrals from counselors at Psychological Services who, in an effort to help students cope with their mental health, recommend they reach out to SAS for support.

“We didn’t get any more staff to accommodate for that,” Feaster said. “So the backlog of students who need accommodations and the level of individual accommodation conversations we’d like to be having doesn’t match the number of staff we have.”

And with Kent State’s university-wide hiring freeze, that will not change anytime soon.

Pamela Farer-Singleton, chief university psychologist at University Health Services, said since 2019, two full-time and three part-time counselors or therapists were added to the Kent Campus Psychological Services staff. While she could not confirm if the number of referrals to SAS have increased since then, she said as a general rule, the more students the Psychological Services staff sees, the more referrals they make.

As of now, two SAS access consultants are responsible for arranging welcome meetings, follow up appointments, and mediated conversations with faculty for the 1,500 students connected with the office. But some students and staff question whether that is sufficient.

Lamar R. Hylton, vice president of student affairs, said the student to staff ratio in the SAS office is “higher than we would want it to be for an institution of our size.”

Hylton said SAS is only one piece of the very large and complex puzzle that is adapting to serve the rise in students who need mental health support and services. Hylton said university faculty and staff members are doing the best they can to do right by students with the resources they have. He also believes this is not a problem the university can simply “hire [its] way out of.”

In the fall, a university-wide committee consisting of students, faculty and administrators convened to talk about services, training and education efforts around mental health, and made a list of recommendations to Hylton’s office. Hylton said because of financial issues, including those brought about by the coronavirus pandemic, Student Affairs has not been able to make headway on those recommendations.

“It’s not because the university doesn’t care,” Hylton said. “But because of finances, especially the financial issues the pandemic has caused.”

Why students with disabilities drop out

Last year, national deaf activist Christine Marshall encouraged people with learning disabilities, psychiatric disabilities, mobility impairment and chronic pain to share why they left school using the hashtag #WhyDisabledPeopleDropout. Of the reasons given, some of the biggest themes were denial of accommodations, lack of support and discrimination. In an interview with The Daily Dot, Marshall said while dropping out might be a last resort for most non-disabled students, it is often the safest and most logical decision for members of her community.

Murphy said in her experience, students who can’t get the support they need end up dropping out.

“And it’s never because they can’t handle the academics,” she said. “It’s always because the professors or accommodations are not willing to help.”

The statistics seem to support Murphy’s observation. The four-year graduation rate for SAS students in Kent State’s 2014 cohort was 35 percent — down 12 percent from the 47 percent four-year graduation rate for the entire cohort.

Feaster said the data shows SAS and non-SAS graduation rates start to even out in six years, which indicates to their office that taking fewer credits over a longer period is more manageable for students with disabilities.

“If you’re in college and you have any kind of disability, you have to work 10 times harder to stay,” Murphy said. “This college was not built for us, so it’s a constant battle to try to get the accommodations you need just to graduate.”

In addition to the attendance modification, students living with severe and unpredictable pain can request deadline modifications, copies of PowerPoints, breaks as needed and note-taking services, an accommodation Murphy uses when she can to help manage her wrist pain.

Professors can deny accommodation requests if they think a modification will affect the intrinsic nature and learning outcomes of the course, a practice that frustrates Murphy.

At the beginning of the spring semester this year, Murphy submitted an attendance accommodation request to the instructor of her applied behavioral analysis class. In addition to living with arthritis, Murphy was recently diagnosed with Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome (POTS), a condition that affects the way her blood circulates and causes her to become lightheaded or pass out. Murphy said when she feels a fainting episode coming on, she has to let some time pass before she can safely walk or drive, which makes it difficult to get to class.

“We just need professors to understand,” Murphy said. “We want to be there, but if we’re unconscious, they can’t expect us to be.”

Murphy’s professor denied her attendance modification request, which meant Murphy would be penalized if POTS caused her to miss class more times than the syllabus allowed. While the professor declined to comment, stating she does not discuss individual student’s accommodations with anyone other than the student and the SAS office, Murphy said her professor told her only students who were physically present would be able to achieve the course’s learning objectives.

Then, the pandemic happened, and suddenly no student could be physically present.

Disability rights activists across the globe have said that watching universities quickly respond to COVID-19 by offering remote learning and allowing assignments to be handed in digitally has exposed academia’s ableism. It makes them wonder, why is learning from home only made possible when circumstances affect the health of the non-disabled majority?

Murphy said if a class cannot be accessed by a person with a disability, then the structure of the class or the syllabus is at fault, not the student.

“When students are denied an accommodation, they feel like they’re being denied because of their health,” Murphy said. “Just because someone has a disability does not mean they don’t have the same right to an education.”

Murphy and Feaster would like to see more professors become familiar with and implement a framework called Universal Design for Learning in their courses. This approach proposes that when professors design courses with the needs of the student most in need of accommodations in mind, it benefits every student and eliminates unintentional barriers.

While non-disabled individuals may view people with disabilities as being a “burden” on society because they’re unable to do things, Murphy said in reality many people with disabilities just need simple supports to accomplish tasks. Employers and universities who provide these supports are helping “create a greater workforce with less people we’re going to have to support financially. I just think people can’t see that,” Murphy said.

Murphy is not the only student who has been denied an accommodation. Brianna Cummings, a senior fashion design major living with Crohn’s disease, a bowel disease that causes severe stomach pain, said a professor at another university once refused to accept late work when she was admitted to the hospital to have a major surgery.

“He was like, ‘Get it done beforehand or get it done on time,’” Cummings said.

She didn’t think it was a fair expectation for a student living with unpredictable health demands.

Feaster said students in situations like this often “feel like no one is fighting for them to succeed.” In response, she often asks the professor, “What do you do for other students who miss class, like your athletes? If you let them make it up, then why can’t you justify the same amount of flexibility for this student?”

Feaster said while she understands there are parts of courses that are non-negotiable, SAS can meet with professors to help identify potential flexible solutions for students.

“We can’t always change a professor’s attitude,” Feaster said. “But we can provide a more enforceable way to have them treat students fairly.”

Fighting isolation with community

When senior nursing major Elizabeth Burger returned from winter break last spring, she could tell her roommate had come down with something worse than a cold. Even though her roommate said she would be fine and didn’t need a doctor, Burger insisted she make an appointment with University Health Services.

Burger has gastroparesis, a disease that prevents the stomach muscles from digesting food properly, and a compromised immune system from a liver transplant she received as an infant. For her health’s sake, she needed to know what her roommate had.

The next day, after a doctor confirmed her roommate had mono, Burger immediately called her transplant nurse who said the best-case scenario would be to get her out of the room that day, since catching mono would almost certainly land her in the hospital for a couple days. Burger worked with residence services to formulate a plan. She would go home to Columbus and miss three days of classes while residence staff set up a new room for her in a different dorm. Burger said though the situation was stressful, and her thoughts were racing, (“What does this mean? What do I do? Can I handle this by myself?”), interacting with staff members who were responsive, helpful and genuinely concerned for her well-being made all the difference.

For Burger, one of the hardest things about living with chronic pain is its invisibility.

“People can’t see any physical effects on you, other than maybe you’re a little bit paler,” she said. “If you have a broken arm, people can see that, and they’re like, ‘Aw, that sucks.’ But when you say, ‘My stomach is literally killing me right now,’ they can’t see that. All you can do is tell them about it.”

Cummings said she constantly feels the need to prove to professors and coworkers she is as sick as she says she is.

“Whenever I have to call off work, I feel like people are like, ‘Oh, she’s sick again,’” she said. “Well, yeah, I’m sick every day. It’s just this day, I’m too sick to work.”

It can be tough to make it through college without friends, but making friends and building a support system when you’re not feeling well is also difficult. Cummings and Murphy said because students with chronic pain typically have less stamina, sitting through classes alone can wipe them out. When that happens, it is easier to stay home rather than go out and socialize.

“And I can’t drink alcohol because of Crohn’s, so that definitely kills your social life if that’s something you want to do,” Cummings said.

This year, Murphy started a chapter of the national organization DREAM (Disability Rights, Education, Activism and Mentoring) at Kent State.

“I was having one of those bad pain days, and I was just so frustrated,” she said. “And I thought, there has to be more people out here trying to make it through college, too. I just don’t know where they are.”

One of the great things about DREAM, Murphy said, is members are able to text each other when they’re not feeling well and know someone’s there, even when they can’t physically be together.

“Not everyone has that support system,” Murphy said. “But I think it makes a huge difference.”

Another thing that has made a difference for Murphy is therapy. She worked with a therapist to learn grounding techniques to cope when she feels anxious or panicked when she starts to feel sick.

“With health, you don’t always have control,” Murphy said. But learning how to manage the anxiety around her health has taught her to say, “No, I have control over this.”

In addition to providing a safe, emotionally-supportive place for students to build friendships and share their lives with others who “get it,” Murphy and the other DREAM officers want to teach students with disabilities to advocate for their own educational needs.

“In college, you can’t bring your parents to meet with professors,” Murphy said. “You are your biggest advocate.”

The DREAM officers are starting a program where they will go with students to meet with their professors and discuss accommodations.

“I’ve advocated for myself for so long, I learned what you need to say in order to get what you need,” Murphy said. “I want to teach that to people so they don’t have to drop out.”

This year, Cummings joined the student organization Glamorous Gutless Girls (GGG), a group that provides financial and emotional support to students living with digestive disorders. There she met Burger, who wants to reduce stigma around talking about digestive issues.

“Some people are like, ‘Oh, I don’t want to talk about poop,’” Burger said. “But it’s something we deal with every day, and it’s fine to be open about it.”

Burger said she wants GGG to be a place for students to come, eat GI friendly snacks and feel comfortable talking about whatever they want.

Two days before Valentine’s Day, Cummings and Burger along with another GGG officer, Erika Sitch, decorated a room in the Kent Student Center with heart garland and festive tablecloths. Cummings set out a spread of homemade gluten free brownies and cookies, dairy free ice cream and sugar free candy along with coloring books and wordsearches.

For two hours, the girls played games, joked around, took pictures, ate and chatted while a movie played in the background. Health wasn’t the purpose or the focus of their gathering, but when it did come up, there was no sense of stigma.

This may be what made a student who dropped in for the first time feel safe enough to confess her frustration with her doctor’s inability to provide a diagnosis for the near-constant nausea she was experiencing. Cummings, Burger and Sitch heard and validated the student’s concerns with empathy.

Feaster said this radical action — when students are willing to get into groups, talk about themselves, put in the emotional work and put themselves out there — is what gives her hope the university’s approach to students with disabilities can change.

“I’m hoping students, faculty and staff begin to see we’re all responsible for each other,” she said. “This is our community. We need to reduce barriers anywhere we can for anyone we can, no matter where those barriers come from. Flashes take care of flashes.”

Hylton said if a student is hesitant to seek help because they know the SAS office is understaffed, they should persist in seeking the help they need anyway.

“We need to know students need help in order to get them help,” Hylton said. “If they do that, it’s up to the university to do the work.”

Lyndsey Brennan is a guest writer. Contact her [email protected].