What you need to know about a potential COVID-19 vaccine

Returning to life as it was before the COVID-19 outbreak may hinge on the development and widespread availability of a coronavirus vaccine. Government scientists, biotech companies and university researchers around the world are racing to develop the first one.

With more than 100 vaccine candidates currently in the works, here’s important information about potential COVID-19 vaccines.

How does your immune system work with a vaccine?

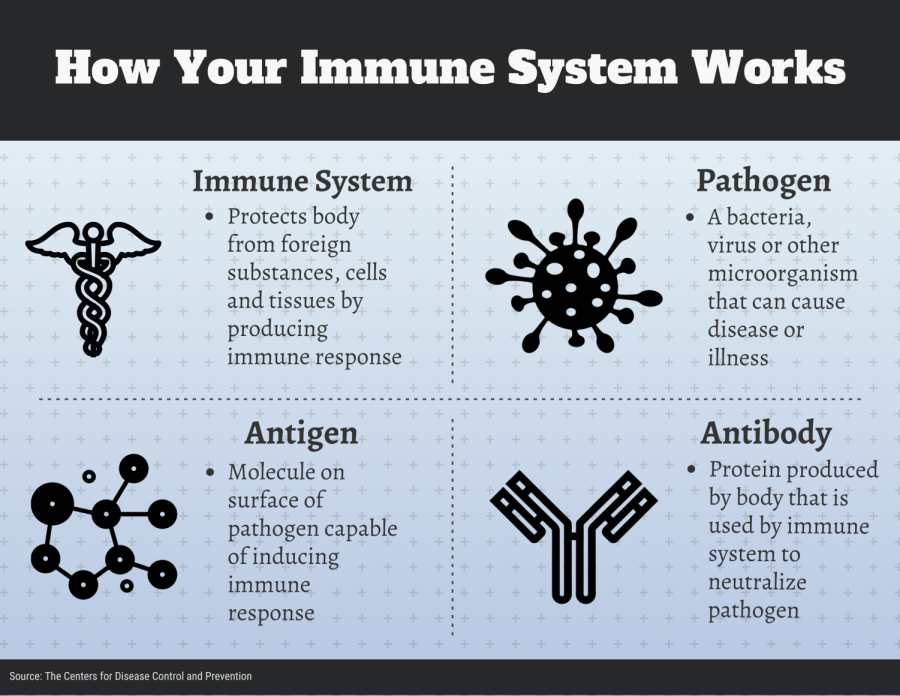

To understand the current landscape for the process to find a COVID-19 vaccine, you first need to understand the role of any vaccine, and that begins with your immune system.

When a disease pathogen enters your body, your immune system’s response is to produce antibodies, said Madhav Bhatta, a professor of epidemiology at Kent State. These antibodies kill the disease pathogen by signaling your body to attack it.

Over time, the immune system keeps track of every virus it defeats. That way, it can recognize and destroy invaders before they make a person ill.

Vaccines circumvent this process by teaching the body to defeat pathogens without the person ever becoming sick.

Essentially, a vaccine teaches the body’s immune system how to handle a pathogen before a person encounters the real thing, Bhatta said.

Types of vaccine candidates

The two most common types of vaccines are live and inactivated vaccines, according to the Mayo Clinic. Inactivated vaccines contain pathogens that were killed while live vaccines are made from pathogens that were weakened (attenuated). Live vaccines tend to be highly effective but are more likely to cause side effects — inactivated vaccines tend to require multiple doses.

There are also new approaches scientists are taking to develop a coronavirus vaccine. Nucleotide based vaccines are made using the genetic code of a molecule on the surface of a pathogen — an antigen.

“Instead of injecting a protein, they’re injecting basically the coding part that tells your body to make that protein. … And it seems to cause people to generate antibodies,” Tara Smith, a Kent State professor of epidemiology. These vaccines are also known as genetically engineered DNA and RNA vaccines.

According to the World Health Organization, advantages to this approach include the stimulation of cell responses, improved vaccine stability, the absence of any infectious agent and the relative ease of large-scale manufacturing.

According to documents released by the WHO, there are currently 124 COVID-19 vaccine candidates — 10 are in human testing trials. Of those, five are inactivated vaccine candidates, two are live vaccine candidates and three are nucleotide-based vaccine candidates.

“It’s really an international development opportunity. So we have a number of groups at universities, at pharmaceutical companies, within the government, all working on different vaccines right now,” Smith said.

How soon will a vaccine be ready?

According to Dr. Seema Yasim, the director of Research and Education at the Stanford Health Communication Initiative, the average vaccine takes 10 to 15 years to develop. The Mumps vaccine was the fastest vaccine ever developed at four years.

The clinical development stage is composed of three phases, Yasim said. In phase one, a small group of healthy volunteers receive the experimental vaccine. This phase helps scientists select a dosage for the vaccine.

In phase two, several hundred people of different ages and health statuses receive the experimental vaccine. A fraction of the group is given a placebo. A placebo is a treatment with no pharmacological or biochemical effect which can be used as a control in clinical trials. This phase helps scientists gauge how effective the vaccine is and control for different variables.

In phase three, the experimental vaccine occurs in natural disease conditions. Thousands of candidates ‒ usually in areas largely affected by the outbreak ‒ receive the vaccine, Yasim said. This phase tests the efficacy of a vaccine against people at a higher risk of infection by the target pathogen.

Dr. Anthony Fauci, the director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, predicts it will take around 12 to 18 months to develop a coronavirus vaccine. This would be the fastest scientists ever created a vaccine.

Smith mentioned scientists are speeding through the research and development stage because of past research done on developing vaccines for Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) and Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS). Both are coronaviruses similar to the current SARS-CoV-2 virus.

“This isn’t something that just completely started in January or February. This is something that goes back to 2003 with the SARS epidemic and starting to develop vaccines around that,” Smith said.

SARS vaccine candidates made it to the clinical trial phase but were never completed due to the fact the outbreak was extinguished and funding to find a vaccine was cut.

“A lot of those [SARS vaccine] candidates have been sitting around now for five or 10 years. Now, they’re being tweaked a bit with new proteins and things like that from this coronavirus. So it’s not like we’re starting completely from scratch,” Smith said.

A compacted timeline, however, does not mean vaccine developers will be rushing through steps.

“Although the timeline may be compacted, nowhere during that process will it not go through the same rigorous process ensuring it works. … Protocols are put in place to measure safety and efficacy,” Bhatta said.

Dr. Smith agreed. “I think we have to remember that we’re not starting from [square one]. Really, we’re using all of that other research for other viruses to apply to this one,” she said.

The race to a COVID-19 vaccine does not follow the traditional process of developing a vaccine. Normally, the steps in the process are sequential in order to mitigate the financial risk. The current process is being accelerated by performing several developmental steps at once.

According to the New England Journal of Medicine, platforms with experience in humans, phase one clinical trials may be able to proceed in parallel with testing in animal models.

The ideal vaccine candidate

The common target of coronavirus vaccines under development are the virus’s spike proteins. “That is the part of the virus that binds to host cells. So if you can get antibodies to that and stop the virus from binding in the first place, you can stop the infection,” Smith said.

Bhatta said researchers focus on two criteria when developing vaccines: safety and efficacy.

When vaccine developers look at safety, they tend to focus on the potential side effects it would have on the humans receiving it.

“They have gone through rigorous testing on their safety to ensure that those adverse events are not significant, that the benefits far outweigh any potential adverse events,” Bhatta said.

Efficacy measures how well the vaccine protects a person from getting sick. Ideally, a vaccine would have 100% efficacy, but many don’t. For example, this year’s flu vaccine measured efficacy was 45%, per the CDC.

“You will have a very small population that will just not become immune with respiratory viruses,” Smith said. “With most of our other ones, the typical vaccines are protective against about 80 to 90 percent of those who are vaccinated.”

Because the first approved vaccine candidate for coronavirus will be developed in record time, its efficacy may be lower, Smith said.

“It may not be as effective [of a vaccine] and something more like the flu vaccine where it’s about 40 to 60 percent effective depending on the year and composition,” she said. This level of efficacy would still make a difference in the current pandemic.

“Even that would help,” Smith said. “If half of the population were immune, that would still decrease transmission in the population, even if it’s not perfect.”

The ideal vaccine will be one scientists deem the most efficient, but it’s not a simple calculation, Smith said.

“If you have one that protects 95% of people but has twice the amount of reactions as another one that only protects 80% of people, you’d have to weigh those things,” she said. “Can you sacrifice some of that safety for a more effective vaccine, or do you go with the one that is less effective, but maybe safer?”

Bhatta said the potential side effects of a vaccine are no cause for worry.

“There are people who tend to think vaccines somehow cause all sorts of problems,” he said. “But it’s one of the most effective public health tools we have. Like any other medications, they carry some potential yet minimal side effects.”

Smith reiterated this statement and said, “Vaccines that have been approved rarely cause serious issues.”

According to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services website, most people who receive a vaccine do not experience serious side effects. One potentially serious side effect listed was severe allergic reactions to a vaccine. Even so, the HHS says out of one million doses of a vaccine given out, the chances of experiencing this is 0.0000015%.

Other minor side effects include redness or swelling of the injection area, a mild fever, soreness and fatigue.

Vaccine development is only one challenge

Health experts would like to vaccinate the entire world population, but that totals to over seven billion people. In the U.S. alone, vaccinating all Americans means supplying treatment to over 330 million people.

“We are going to need 300 million doses if we just require one dosing. If we require two doses, then you double that number. … If everything falls in place and you have a vaccine, you still have to deal with the production and distribution and implementation of that,” Bhatta said.

The issue of manufacturing such a large number of vaccines has to do with both time and money. A company spokeswoman for pharmaceutical company Pfizer stated it took five years and $600 million to build a vaccine manufacturing site.

The Trump administration recently rolled out Operation Warp Speed. The goal of the operation is to meet President Trump’s call to develop 100 million doses of a SARS-CoV-2 vaccine by November 2020 and 300 million doses by January 2021.

The newly created program ties together all major federal, medical and oversight entities and the military, into one massive coordinated push for a vaccine and treatments. While promising, it is still unknown if such a goal will be met.

Who should get a vaccine?

But the benefits of a vaccine are more far-reaching than just the individual who receives it. “I think vaccination is not only that individual’s decision. You know, do I get this to protect my community as well? And that’s what I hope people will be thinking about even if they’re not at a high risk,” Smith said.

Smith referenced a form of indirect protection from disease known as herd immunity.

Front line workers and high-risk groups are logically those in most need of a potential COVID-19 vaccine. Yet, Smith said everyone could benefit from receiving one.

“I think it’s hard for the young and healthy people to want to get it because they’re not the ones who are usually most seriously infected,” she said.

According to the CDC, herd immunity is a situation in which a sufficient proportion of a population is immune to an infectious disease (through vaccination and/ or prior illness) to make its spread from person to person unlikely.

Smith said a potential COVID-19 vaccine will not only be effective in protecting individuals but also in creating a herd immunity situation in the pandemic.

According to the CDC, those over the age of 65 are at a higher risk of severe infection from COVID-19 as compared to younger age groups.

Even though the younger population is not considered high-risk for severe illness from coronavirus, Smith said infections can be unpredictable.

“For me, I think it’s just kind of gambling with your own health to assume that you would be one of those people who would only get a mild infection if you’re exposed to the virus,” Smith said.

Contact Connor Steffen at [email protected].