Students, administrators discuss how they’ll address racism, hate speech at town hall meeting

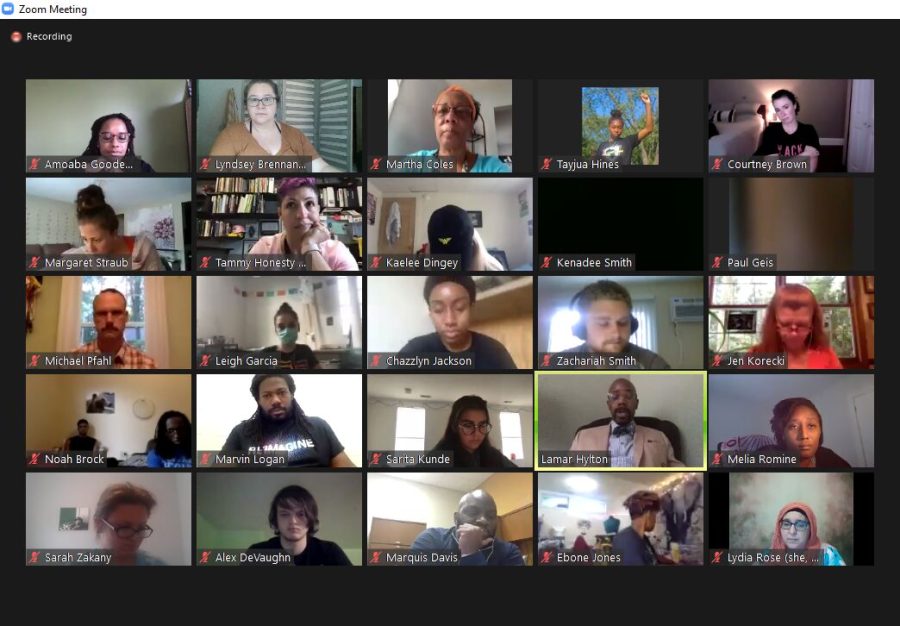

Two hundred and fifty eight Kent State administrators, students, faculty and alumni attended a virtual town hall Thursday organized to address what administrators and student organizations are doing about racism on campus after repeated racist messages were left on the rock.

One goal of the town hall, which was organized by Black United Students, the Undergraduate Student Government, the Division of Student Affairs and the Division of Diversity, Equity and Inclusion, was to bring students up to speed on how the university is addressing BUS’s demands to Kent State President Todd Diacon.

Since BUS released its demands on Sept. 8, the university has met two out of seven, said BUS president Tayjua Hines. Those demands are that the university:

-

Release statements on its website, along with emails, clearly denouncing any hate speech and discriminatory actions and

-

Update its security escort webpage to reflect new hours.

The university has acknowledged the other demands, Hines said, and is currently working with BUS to determine how to implement them.

Regarding the demand that the university add an anti-hate clause to the code of conduct, Hines said she is in conversation with Lamar Hylton, Kent State’s Vice President for Student Affairs, to “see how we’re going to move through that.”

In response to the demand that fully uniformed Kent State police officers no longer respond to mental health crises, Hines said Hylton is looking into how that can be implemented in terms of the budget, because it would require adding trained mental health practitioners to the staff.

In addition to addressing BUS’s demands, the university has taken several action steps of its own to address the racism seen in the last weeks, said Hylton.

Dean of Students Taléa Drummer-Ferrell has approved a full-scale review of the student code of conduct, which will bring together faculty, staff and “a good representation of undergrad and graduate students to make sure we’re looking at our code through a lens of equity, inclusivity, and justice,” Hylton said.

The committee’s deadline to submit recommended changes will be Oct. 15. Hylton said Drummer-Ferrell will determine if and how students who are not a part of the review group can submit feedback.

Hylton said the university will also launch a security review of the entire campus and put together a group to develop policy language about the rock’s intended use and purpose.

A tentative date of Sept. 22 is set for the first meeting of KSU’s Anti-Racism Task Force, said Amoaba Gooden, Kent State’s Interim Vice President of Diversity, Equity and Inclusion. The task force will have 15 subcommittees and leverage recommendations made by the ad-hoc on race committee Gooden co-chaired last semester. If students want to be involved in the task force, Gooden welcomed them to reach out to her or another person in the DEI office.

She is also in the process of reviewing the way the university conducts its equity, diversity and inclusion audits across divisions so that each one can be held accountable for making progress in that area.

“This work can’t live in one division. We have to see it lived throughout all units, all spaces on Kent State’s campus,” she said.

As a sign that the university is embracing change on an institutional level, Gooden mentioned President Diacon’s commitment to allocating $1 million per year to diversify Kent State’s faculty for the next 10 years. When students asked why Diacon didn’t attend the town hall, Gooden explained he was in a board of trustees meeting, reviewing financial documents and policies that are due to the board Wednesday.

Gooden has also been in talks with Provost Melody Tankersley about mandating all incoming faculty and staff go through social justice training—but, Kent State would have to work with the union in order to make this training a required part of the contracts for both tenured and non-tenured professors.

Melia Romine, a first-year PhD student studying biomedical science who attended the town hall, said she wished administrators would have provided more details about the scope of the task force and what the university hoped to accomplish through social justice training.

“Some faculty don’t take trainings seriously,” she said. “You have to want to change when you’re taking a workshop.”

In her experience at Kent State, where she earned both her bachelor’s and master’s degrees, faculty have been reluctant to address racism. But if students can’t feel comfortable approaching their professors when they experience discrimination, who can they go to?

When addressing racism in academia, administrators need to place their attention on the faculty, she said. “It starts from the top and trickles down. If higher-ups start cracking down on discrimination, you start to build a shield over the students it affects,” she said.

Throughout the town hall, some of those in attendance used the chat function to make racist comments. They were promptly removed from the Zoom call, and students suggested administrators use a function in Zoom to trace the IP addresses of those who disrupted.

At one moment in the meeting, Hines and a faculty member addressed those racist comments.

“The rock has been basically a tool to bring everything out that’s going on that black students have been talking about since we got here. And that’s why we’re here for this town hall,” Hines said. “We not here ‘cuz people painted, ‘White lives matter’ and ‘Blacks have no home here’ on the rock. We’re here because there needs to be systemic changes at this university, and the rock was showing everyone at this university what we’ve been talking about. Removing the rock is not removing the problem.”

Gregory King, an assistant professor of dance, added, “Think about it: We’re here to talk about the rock, and there are people who are still finding their way into the space where we are creating change—are asking for change—and they are saying ‘eff you’ to every single one of us because they feel okay doing that. There’s a sense of emboldenedness—that’s the problem. They feel that it’s okay to behave that way, because in their minds Kent State for too long has okayed that behavior.”

After discussions with leaders at Youngstown State and Wright State who have also had to contend with hate speech and racial slurs, USG president Tiera Moore said, “We believe that this is an issue that’s going to continue as the tension heightens with the election.”

In the instances to come, the First Amendment will likely protect those who make racist statements, said attorney Michael Pfahl, associate counsel at Kent State, who also attended the town hall.

There are some exceptions, though—for instance, speech that incites others to take imminent lawless action, harassment that is so severe that it denies a victim access to education, or speech that does direct injury to a direct person (known in lawyer-speak as fighting words).

Students wanted to know if statements like “Blacks have no home here” or #SilverMeadows, which Moore said refers to an instance where law enforcement shot and killed a Black man, would fall under one of those exceptions. If a student feels threatened, is that speech protected?

In order for the court to justify limiting speech, Pfahl said, the speech must “include something beyond the mere expression of views, words, symbols, or thoughts that some person finds offensive.”

That is, it must be “considered sufficiently serious to deny or limit a student’s ability to participate or benefit from their educational program. When you’re talking about just mere utterances … those tend to be protected,” he said.

Earl Lane, a sophomore theater major who attended the town hall, said when he heard Pfahl’s answers, he felt like there was no solution. It seemed like Pfahl was saying, “Someone has to get harmed for someone to do something. No one wants to hear that.”

Kathleen Tyrel, a junior ASL/English interpreting major, felt similarly. “I didn’t hear much about how the school plans on doing something about damaging rhetoric. I heard a lot about talking and discussing, but not a lot of applied action.”

She said she thinks administrators are “bound by too much red tape and politics to really be able to help in the way I’m sure they want to.”

While Lane found the meeting informative and well-intentioned, he said buzzwords like “task force” can be either misleading or confusing and unclear for students.

Ultimately, he said he didn’t feel convinced that a solution is on its way. “I don’t feel like we got anything done. We were trying to come up with a solution, but we didn’t figure anything out. I feel like we started and ended in the same place.”

“Our Black students really need to feel secure, and at this point, most of us just don’t.”

Contact Lyndsey Brennan at [email protected].