KSU professor searches for his mother, a Holocaust survivor

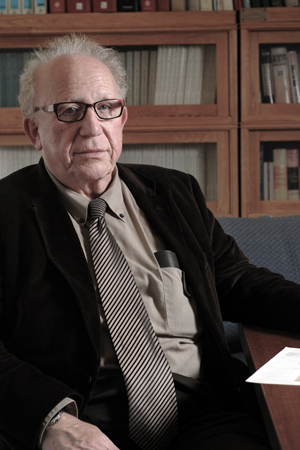

Sol Factor taught a class at Cleveland Heights High School, where he met a German exchange student who helped him trace his mother. Factor has taught Jewish studies classes at Kent State since 2006. Photo by Matt Halfey.

Rosa Pollak is a Holocaust survivor. She spent time at Auschwitz, the concentration camp where millions of Jews died at the hands of the Nazis. If she is still alive, she is 87 years old and living in Israel. At 10:22 p.m., June 28, 1946, in Munich, Germany, she gave birth to a son named Meier Pollak.

This is all Sol Factor knows of his mother — the same woman who refused his request to meet her more than 60 years later.

His electric blue eyes beam as he runs his fingers over a folder of documents — the only link he has to his birth name and his birth mother, whose faded signature is the only remnant he possesses.

He reads through frank descriptions of himself as a child written by various social workers who clearly didn’t think he might one day read through them.

“’Meier was not a pretty baby, but he was appealing in that although not babyish in facial contour, he had definite features from which could be visualized a future Mickey Rooney appearance,’” he chuckled as he read the description of himself as an infant. “I find that absolutely hilarious.”

Factor has just one photo of himself as an infant, taken in a German airport just before he was transported to the United States.

“I was apparently quite underweight and neglected,” Factor said. “Can you believe they said, ‘He’s still a little retarded both mentally and physically?’ I think I more than made up for it.”

Factor, whose curly red hair has since turned to gray, was adopted in 1950 by a Jewish couple in Belmont, Mass. Dr. Joseph Factor and his wife, Bernice, who were unable to have children of their own, had been trying to adopt a Jewish child from Germany since the outbreak of World War II.

When he was officially adopted in 1950, Factor said he could remember sitting on the judge’s lap as he became a U.S. citizen and had his name officially changed to Sol Factor. He said he led a normal childhood, and his parents never tried to hide the fact that he was adopted.

“My mother’s response always was, ‘Adoptive parents really want their children if they have adopted them,’” he said. “Some kids could care less who their real parents were. Some kids, it’s an obsession, and they’re never comfortable. I was fine.”

The search

In 1990, after a lifetime of unanswered questions, Factor finally started trying to reconnect with his birth mother, a search that would last nearly 17 years.

“I decided I wanted to find out, not so much for myself, but for my children,” he said.

When he began his search, both of his adoptive parents were still alive, and he never told his mother what he was doing.

“My mother was dying,” he said. “I never shared with her my desire to do this mainly because I think she would have been hurt. Eventually I shared with my father what I was doing, and he understood.”

Before teaching Jewish Studies at Kent State, Factor worked at Cleveland Heights High School, where he taught a course on the Holocaust. Until 2001, he made little progress in his efforts to find his birth mother.

“In 2001, this young (German exchange student) became a student in my homeroom and in my Holocaust class at Cleveland Heights High School. I always shared with my classes my story,” Factor said. “He told his mother, Claudia Zachmann, my story. And she emailed me, ‘Could she help?’”

Zachmann and her two sons spent their vacations traveling to Munich searching for any information that might give them a lead to Factor’s birth mother. Through old records and documents, Zachmann was able to trace Factor’s birth back to the Frauenklinik in Munich, a former displaced person’s hospital following World War II. She discovered documents detailing Factor’s eventual transfer to the United States as one of many orphaned and unaccompanied children and found out he had been separated from his birth mother at just two weeks old.

“I never did something like this before for anybody else. It was a very special history lesson for myself, aside of the fact that I wanted to help a friend,” Zachmann said. “I did not know anything about genealogy and family research when I started. I just began to look at the nearest possible place and then things developed in their own dynamic way.”

With these leads, Factor filed a report through the American Red Cross Tracing Center. He was hopeful that he was finally getting close — until he got a call from a social worker with disappointing news: She would not meet with him.

“I always said that the choice would be hers,” Factor said. “How would you feel if for whatever reason you gave up a child, and 60 years later, they’re in your face? It had to be tough. I have to believe it had to be tough.”

Zachmann, too, shared in Factor’s disappointment.

“I felt so sorry for Sol,” she said. “Also a meeting between mother and son after such a long time would have been somehow a completion of all the work we had done so far.”

Although he was disappointed, Factor said he never had a moment of weakness until he was giving a presentation at a memorial center in Israel last summer. When he told the group about his letter from the Israeli Red Cross, Factor said he finally broke down.

“It was a combination of dealing with the reality of not making the contact in person and the reality of sitting at Yad Vashem, the memorial center for the Holocaust in Jerusalem,” he said. “I think it was where we were, and it was the toughest thing to get through. It was just knowing where we were.”

Moving on

While Factor doesn’t think he’ll ever know for sure why his mother refused his request, he suspects that she may have remarried and never told her new husband about her child. He also realizes that meeting him might bring up terrifying memories of her days in Auschwitz, which she may have been trying to mask all these years.

“Sometimes some of these survivors are tough to deal with. They are territorial — ‘It’s my way or the highway,’” he said. “On the other hand, you have to say if they didn’t have this toughness, they wouldn’t be here. That’s the other side of the coin.”

To this day, Factor still has many unanswered questions. On his birth certificate and other records, Rosa Pollak, originally from Romania, said she married Schaja Pollak on June 7, 1945, a few months after the liberation of Auschwitz. She said he died in October of 1945, exactly nine months before his supposed son was born. To date, however, Factor has never found any written documents or proof of their marriage.

“More than likely she might have had a relationship with another survivor, and the relationship ended when she became pregnant with me,” he said.

Although there are many loose ends still left untied, Factor said he has closure in at least knowing some details about his past.

“I did have offers to have private investigators for a fortune,” he said. “She made the decision. That’s her decision. I hope that if she’s alive, she can live with it.”

Factor said when he gets some free time, he may return to Israel and make one final attempt to find the woman he has so many questions about. If he ever does find her, he knows what he’ll tell her.

“Probably I would share with her what’s happened to me,” he said. “I’ve been married for 40 years, lovely family, lovely grandchildren. And above all, I’m not bitter.”

Contact Leighann McGivern at [email protected].