KSU makes strides in the battle against peer-to-peer illegal downloading

In 2007, Kent State ranked No. 17 on the Recording Industry Association of America’s list of the top 25 music-pirating schools in the country.

Today, after the implementation of new policies and procedures, most of which are preventative, the university is more successful at preventing peer-to-peer, better known as P2P, file sharing among students on campus.

“It’s been a gradual downhill incline,” said Kimberly Price, senior IT security analyst for Kent State’s Office of Security and Access Management. “Part of that is the education we put in. We started meeting with students, explaining, ‘Hey, this is how this works. Did you know that?’ Most of them have been pretty receptive to it.”

In 2006, the first year Kent State started tracking P2P activity, there were 409 infringements filed by organizations like the RIAA, the Motion Picture Association of America and others, claiming copyright violations by Kent State students in everything from music to movies to computer software to pornography. As of mid-November 2011, there had been 234 cases of infringement filed by copyright owners for the year. Although those numbers aren’t ideal, Price and others at Kent State view the downward trend overtime as a success.

Price said the dramatic decrease in infringements can be credited to the university’s proactive approach at preventing illegal file sharing, which started just before the passing of the Higher Education Opportunity Act in 2008. This legislation requires colleges to implement controls against P2P exchanging of copyrighted material or risk losing federal financial funding for students. Enforcement of the law began in July 2010, but Kent State put new measures in place in 2007 shortly after the RIAA ranking was published. The university’s new strategy focused heavily on informing students of the laws and dangers of illegal downloading.

“We were way ahead of the game before we were made to,” Price said. “Part of the problem was students just didn’t know. It’s something they grew up with from a long time ago. As all the laws are changing, information just doesn’t seem to get out. So we started doing education, and I think that’s made the difference.”

#KWpiracy

new TWTR.Widget({

version: 2,

type: ‘search’,

search: ‘#kwpiracy’,

interval: 6000,

subject: ”,

width: 240,

height: 300,

theme: {

shell: {

background: ‘#b8b8b8’,

color: ‘#66a9c5’

},

tweets: {

background: ‘#b8b8b8’,

color: ‘#444444’,

links: ‘#1985b5’

}

},

features: {

scrollbar: true,

loop: true,

live: true,

hashtags: true,

timestamp: true,

avatars: true,

toptweets: true,

behavior: ‘default’

}

}).render().start();

Educating freshmen

One of the biggest deterrents has been a presentation called “Online Living and Learning,” which every freshman student over the past two years has attended as part of the Destination Kent State overnight summer orientation program. It is given by a Kent State graduate—and former “infringer”—who was caught illegally downloading TV shows on campus as a student in 2005.

“I walk them through the fact that the recording industry doesn’t care about them at all,” said Michael Vaughn, associate educational technology designer. “They’re pretty ruthless about protecting their copyrighted material. They have every right to do that. They’re just very aggressive in some instances. I walk them through what happens if they get caught and the process they go through.”

Zach Brown, freshman exploratory major, attended Vaughn’s presentation last June and said the orientation was effective for him because he hasn’t illegally downloaded anything on campus to date.

“They kind of use scare tactics on us,” Brown said. “They tell stories about kids who downloaded stuff then got sued by record companies for outrageous amounts of money.”

While Vaughn wasn’t sued for the two TV episodes he was caught downloading as a student in 2005, he was placed on disciplinary probation by Kent State and had his campus Internet service taken away for six months.

“My whole goal is to just be aggressive with them [freshmen] ahead of time so they understand,” Vaughn said. “I think the students are getting a little bit wiser about the fact that they can’t download on campus. I do think the preparation over the past two years has helped a little bit. I like to think it has an impact.”

While Brown avoids P2P file sharing at school, he said he still downloads music illegally off campus when he’s at home.

Kimberly Price said many students do that but sometimes forget to close a download or upload when they come back to campus and log onto the university Internet.

“The moment it hits the network, it connects,” Price said.

Technological weapons

Organizations like the RIAA and MPAA use multi-million-dollar software to monitor illegal downloading or uploading of its copyrighted material. Once violators are identified, they send notifications to Internet services providers, like Kent State, demanding a “cease and desist” of all illegal activity by threat of legal action.

“We’re not a policing university,” Price said. “There’s not enough of us to go around to take care of it, but all our servers have logs. We keep logs of everything … We have the ability to see this stuff. We just don’t do it until we get [the notices].”

When a copyright claim is sent to Kent State, it is either just an infringement notice or a settlement offer, which gives an offending student the option of paying a fee up front to avoid a lawsuit. The copyright agencies send the university a description of the infringement, which includes an IP address, a time stamp and the actual name of the file that was illegally downloaded.

“We match that to the logs and the network’s activity of who was using that IP at that time,” Price said. “We have to make sure that we pinpoint exactly who was doing it at that time. We’re very touchy about that. We make sure, for sure, and it’s very time-consuming.”

Kent State’s placement on the RIAA’s worst copyright infringers list was an “eye-opener,” according to Price, that led to the implementation of technologically preventative steps by the university. One is a process called “traffic or packet shaping,” which limits Internet bandwidth for P2P file sharing and makes downloading on campus slower.

“Think of it as a four-lane highway,” Price said. “And all the lanes are going fast. You have stuff that you have to get from point A to point B.

Because some of you guys are carrying things that you shouldn’t, the packet shaper squeezes those four lanes, funneling them down to two. We have that in place, and it works.”

Price made a point of saying the technology doesn’t stop P2P, because “file sharing, itself, is not illegal if you’re file-sharing the right things.”

The consequences

When a student receives a copyright infringement notification, his or her Kent State Internet access is blocked by the university until all stolen files are removed from their computer and an educational course about online piracy law is completed. That includes watching two eight-minute informational videos, reading about the copyright laws and scoring a 100 percent on a quiz about the topic. Repeat offenders have to go to the Office of Student Conduct and face possible suspension.

While most students who get caught are more than willing to comply with the university’s demands, John Paul Kleem, junior nutrition and food major, was not. When Kleem was a freshman in 2009, his Internet access was taken away after one of his friends was caught downloading a movie, logged onto the Kent State network under his username.

“They sent me an email, which is ironic because I couldn’t use the Internet,” Kleem said. “There was a really long process. I took one look at it, and it was so much that I just didn’t even bother.”

Kleem said for the rest of his freshman and sophomore years living on campus he used the Flashline login information — which is good for 10 years — of another friend who went to Kent State but dropped out shortly after Kleem’s incident occurred.

Price said the RIAA started a big push to target university student offenders in 2007 when it began focusing more on colleges and less on the average non-university residence.

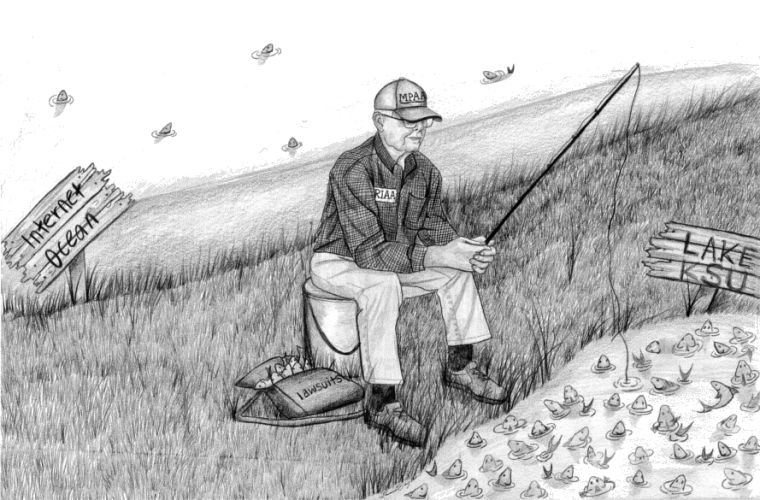

“If you’re going to go fishing, you fish where the fish are,” she said. “You’re sitting here at Lake KSU, and it’s a stock-pond, because new fish come in every semester. The old fish know when to bite and when not to bite. The new fish bite all the time … You’re definitely at risk here, but it’s the luck of the draw.”

Kent State received 21 pre-settlement letters from the RIAA in 2007, giving each student just 20 days to decide if he or she wanted to settle outside of court or risk a lawsuit. At that time it was $3,000 per student, regardless of how many songs were illegally downloaded.

A cyber war

Price said she sees a trend that favors entities like the RIAA and other copyright holders. One piece of legislation that’s currently being debated in Congress, the Stop Online Piracy Act, would make websites legally responsible for any pirated material that they possess or publish.

The government could then go ahead and shut the infringing site down at its own discretion.

A few prominent websites, notably Wikipedia, shut down their services for 24 hours on Jan. 18 to protest SOPA. The following day, the U.S. Department of Justice shut down popular file-sharing site Megaupload.

“It’s really going their way right now,” Price said. “Federal law is really taking a hard look at it, and I don’t think it’s over. I think you’re going to see more changes happening.”

According to Vaughn, however, students are still able to find loopholes that make some downloading untraceable.

“They’re finding other ways that, while still not legal, are more difficult to track,” Vaughn said. “One thing I’m seeing is students ripping songs directly from YouTube, and technically there’s no way to track something like that. It’s lower quality, but they really don’t care.”

Vaughn views the crackdown on Internet piracy as an opportunity for “greater and easier access to cheaper media.”

He said he sees the emergence of inexpensive choices like Netflix, Amazon Prime and Google Music as having a bigger role in reducing copyright infringements than the education he and Kent State actively provide to students.

“I think in the grand scheme of things,” Vaughn said. “As services become simpler, ubiquitous and affordable, that’ll have the greatest impact. At least that’s my feeling.”

Contact Mike Crissman at [email protected].