Analysis of the gender gap in Kent State majors

As the Automated Manufacturing meeting in Fall 2012 came to a close in the College of Applied Engineering, Sustainability and Technology last semester, President Lefton had one last remark to offer: “We need some women.”

The presenting team, which had been entirely male, seemed to nod in agreement.

Gender as a minority status

Just past noon every Tuesday, freshman pre-nursing major Elizabeth Parsons arrives at her psychology lecture. In no time, a murmur of conversation surrounds her, stemming from the voices of men and women from many different majors.

Wednesday brings her back to the same lecture hall. Although the room is filled with familiar, casual discussions, her biology class full of mostly nursing majors has a different atmosphere. The chatter seems to have moved up an octave.

There are few male voices.

Parsons’s lecture hall observation highlights a persistent trend in higher education. According to the university’s fifteenth day enrollment statistics, 1,279 women are enrolled in the College of Nursing this semester compared to only 235 men. Men, therefore, are statistically outnumbered.

“An idea that every male has embraced is that you’re a minority,” said Joseph Fisher of the nursing gender gap. Fisher is a nursing lecturer at Kent State and works at Akron General Medical Center.

Similarly, the College of Applied Engineering, Sustainability and Technology holds more than six times more men than women in the Spring 2013 semester.

Professor L. Gwenn Volkert, the only female computer science professor on the Kent campus, said the technological fields were once populated by both men and women. However, she has become a minority among faculty in recent years as men gain an increasing majority.

She said while the number of women is increasing in technology classes that are not major-specific, they are still rare and often insecure.

“I could probably only name three women that I’ve met within the major,” said Chris Conry, a senior computer science major. He said the gap did not bother him personally, but it could not be ignored.

In Conry’s major, women made up only 24 percent of the nationwide total in the 2009 – 2010 school year, according to U.S. Department of Education statistics.

The report also revealed engineering and technology fields to be largely dominated by men across the nation. Almost 90 percent of undergraduate students in the field were male.

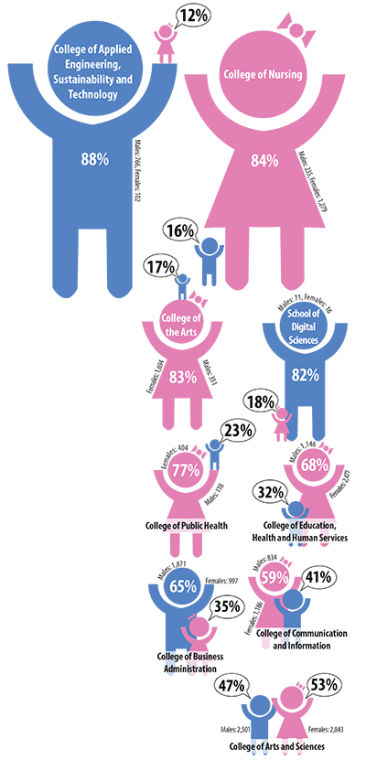

Colleges with the largest Gender Gaps:

*According to statistics from the Kent State Research, Planning and Institutional Effectiveness

At Kent State and professional settings throughout the nation, certain fields are almost entirely dominated by one gender. Analysis of the gender gap in areas like computer science and nursing brings the issue national attention.

College of Nursing

Males: 235, Females: 1279

College of Education, Health and Human Services

Males: 1146, Females: 2477

College of the Arts

Males: 351, Females: 1694

College of Applied Engineering, Sustainability and Technology

Males: 766, Females: 102

College of Business Administration

Males: 1871, Females: 997

College of Arts and Sciences

Males: 2501, Females: 2843

College of Communication and Information

Males: 834, Females: 1186

College of Public Health

Males: 118, Females: 404

School of Digital Sciences

Males: 71, Females: 16

Why does the gap exist?

“Nobody really had a definite answer,” Conry said, observing that class discussions on the topic generally hit a dead end. “It’s not that women couldn’t do it, they just aren’t present.”

Parsons said when she attends meetings of the Students for Professional Nursing, she often wonders what drew the male attendees to the field while others hang back.

For some, it can simply be a matter of entrenched competition. Fisher said a stigma had followed men first entering nursing because female nurses felt their jobs were at risk and became defensive.

“The idea that you’re trying to step on my throat before I even get out of the gate is a problem,” Fisher said, describing sexist comments from colleagues, which he called the most “damaging” of his career.

“Resentment is still alive and well on the floor,” Fisher said.

However, Fisher also said some men may avoid the field simply because they fail to realize its potential or feel they are better suited for other positions in health care. Men, he said, will tend to fill executive positions, where they are the majority, before experimenting with the nursing field, where they are the minority.

Along with competition and a natural attraction to other fields, stereotypes remain a problem and some claim these are equally responsible for the gender gap. Volkert said women find it more difficult to engage in the “celebration of the geek” that men embrace.

“Not all computer scientists, you know, sit around in dark rooms and write programs all the time,” Volkert said.

Women, she said, take on a “less risk” behavior and refuse to tackle the unfamiliar, especially at the risk of being branded a “geek.” Men, meanwhile, have become familiar with technology through the popular gaming culture and therefore feel much more comfortable behind a computer screen, said Volkert.

There are two sides of the stereotype battle. While Volkert says women want to avoid the dreaded “geek” identity, men are plagued by their own barrier of prejudice.

“People assume that guys are in nursing because they weren’t smart enough to be doctors,” Parsons said. Fisher voiced a similar opinion. He said in his 20 years of nursing experience, he has frequently faced the stupidity stereotype and has been asked about his sexuality.

With stereotypes and traditional gender dominance embedded in such fields, the gap is not likely to disappear quickly, said Fisher.

Will things change?

As the education system continues to adapt to the pace of the 21st century, it may be forced to lose its traditional gender majorities for the sake of innovation. In some universities, a shift has already begun.

The Women in Engineering ProActive Network presented the Women in Engineering Initiative Award to Colorado State University earlier this year, according to an article in the Women in Academia Report. The university had reportedly doubled the number of female engineering students since 2007.

While some find this report encouraging, others say intentionally forcing a gender balance is unnecessary.

“If it changes, it changes,” Fisher said simply. Because nursing is a successful practice, a mandated change is unnecessary, Fisher said.

While scholarships have enabled gender-minority students to reach unexplored majors for years, they also raise concerns of fairness to those genders that dominate the field.

“Innovation can just get better,” Conry said, “But you can’t really force it.” The computer science major said an integration of genders is something he believes should happen naturally, without too many scholarships and initiatives.

Soothing students in the divide

Volkert said she hopes an increasingly technologically savvy education system will make women more comfortable exploring computer science. She also said women will eventually realize the potential of fields like computer science to “help” humanity no less than the traditionally female nursing programs.

“Once women recognize that actually computer science is a ‘helping’ profession too, you’ll find a lot more women going ‘Oh, well maybe I will consider it,’” Volkert said.

On the subject of equal pay, experts try to give students the tools to navigate a gender gap fairly.

For counselors in the Career Services Center like Staci Hayes, negotiating a fair salary in fields with a gender majority is key to encouraging student success regardless of the gap.

“Hopefully, in the next couple of years, we’ll see more of an equalizing of race, gender and background,” Hayes said.

Contact Hannah Kelling at [email protected].

Additional reporting by Kirsten Bowers.