The power of words

Editor’s note: This story has been modified from its original version to reflect accuracy in sources.

Microaggressions are subtle and unintentional forms of racial discrimination, said Morgan Rasmus, professor of psychology at Columbia University, who studies their effects in educational settings.

They’re either words or actions, such as calling a Latino-American person “white,” locking a car door when an African-American person walks by or assuming that any non-white person is foreign-born.

“When you ask someone if they’re racist, the automatic answer is almost always going to be no,” Rasmus said, “but many people continue to perpetuate racial biases and engage in racially degrading behaviors in the form of microaggressions.”

Jesse Policy, a Caucasian sophomore computer science major, considers himself a perceptive person, but when he commented on his African-American friend’s love of stereotypical “white” music, he realized being culturally aware goes beyond avoiding racial slurs.

“I’ve always thought I did a good job of being sensitive until I accidentally upset my friend by saying she listened to ‘white’ music,” Policy said. “She immediately let me know how it made her feel and told me she wasn’t upset with me but just wanted me to know. Of course I felt terrible, but it goes to show just because we think we aren’t racist doesn’t mean we can’t say potentially insensitive things.”

Policy’s friend, Stacy Moore, a sophomore business major, took the situation as a chance to enlighten him on how seemingly innocent comments can be offensive, especially when the person isn’t a friend.

“Obviously I know Jesse wasn’t trying to hurt me when he said what he did, but it still upset me,” she said. “I understand as a white male, he’s rarely — if ever — on the receiving end of a racist comment, so he’s not as aware of the little things people say that are offensive to minorities. The only reason I said something is because other people may not know him as well as me and think he was purposely being rude, when in reality he just wasn’t thinking.”

Microaggressions like the ones Sales and Moore experienced present a problem for minority students because they’re often unsure of how to respond. They’re afraid speaking up makes them seem “overly sensitive,” but that it will continue if they don’t address the issue.

Federico Subervi, a journalism professor who specializes in Latin media, said every minority student’s reaction to microaggressions differs depending on a multitude of factors including who’s saying it, how often it’s said and the environment in which it happens.

“Each and every one of us has a level of tolerance,” he said. “At times it may just be how you woke up that day, but also depends on if you’ve been experiencing them on a consistent basis.”

Michael Weisel, a junior sports administration major and president of the Native American Student Association, relies on pride in his Native-American heritage to push through racially insensitive situations without addressing those saying the microaggressions.

“When people call me names like ‘redskin’ or ‘red’ it hurts, but I take myself out of the situation and calm myself down so I don’t take it to heart,” he said. “I handle those situations by looking past it and telling myself I am proud of who I am and my heritage.”

Jinre Holman, a senior accounting major and president of the Spanish and Latino Student Association, was called “white” by Caucasian students in high school because her classmates thought she defied racial stereotypes by taking advanced courses. She also chose to stay silent.

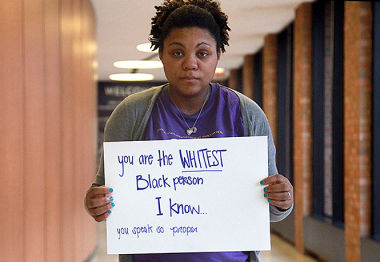

“They called me the ‘whitest black person’ during all four years of high school because I was in tough courses and did not fit many of the stereotypical attributes of being black,” she said. “I handled it the only way that I knew how at the time: I let it happen.”

Other students, like Camara Rhodes, a sophomore theatre studies major, believe the only way to combat microaggressions is by speaking up and letting people know when they’ve committed one, such as when a stranger assumes she only sings gospel music because she’s African-American.

“I never let it slide when it comes to racial things,” Rhodes said. “The reason why people continue to keep racist language is because minority students don’t call them out on it like I do when people assume I’m a gospel singer. It’s not to be rude or harsh but because students need to learn to not be afraid to bring something up if it makes them feel uncomfortable — that’s when things will begin to change.”

Contact Michael Lopick at [email protected].