The art of mindfulness: a practice for some, study for others

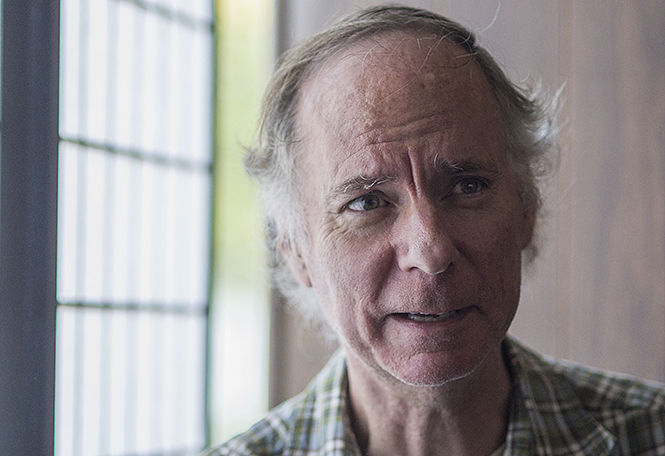

Tim McCarthy, owner and founder of the Kent Zendo in Downtown Kent, focuses on practicing “minfulness meditation.”

In a little pocket of the University Plaza, among vacated stores and former beauty parlors, sits the ever-so-humble Upaya Zen Center. Inside sit little Buddha statues dotted in between meditation pillows and Zen poetry on the wall. Books like The Art of Living lay on a bookshelf above containers of Dandelion tea. Tim McCarthy, the leader of the Zendo, sits in a full lotus position in the corner of the room, smiling like the Buddha.

“Some people say I’m too friendly for a Zen teacher,” he says.

McCarthy, who has been running the Upaya Zen Center for the past six months, is also the founder of the Kent Zendo community on campus. As a teacher of Theravada Buddhism, he is trained in the fine art of what is called “mindfulness meditation,” which is simply defined, he said, as the zazen practice of “being aware of what already is there.” Just as Buddhism itself has many interpretations — which may even lead to “arguments” among practitioners — so does the word “mindfulness” itself. It’s practice is something McCarthy is sure to include in his daily session.

Others want to bring it to the lab.

On September 4th, Congressman Tim Ryan announced a $3.7 million grant awarded from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health to Kent State professors of psychology David Fresco and Joel Hughes. The award money will fund their five-year study called “Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction for High Blood Pressure.” Observing and recording data from 180 Ohio patients, Hughes and Fresco will attempt to prove that the practice of mindfulness-based meditation is a certified cure for anxiety.

This idea of “prescribing” what McCarthy already practices, Hughes said, doesn’t need to be recommended by a doctor to be a stress-reducer. But defining it a “medicine” is a whole different ballgame.

“People, of course, can do whatever they want,” Hughes said. “But as soon as we want to start saying ‘this works’ and ‘that doesn’t work’ — that’s when the science comes in.”

Hughes, a specialist in cardiovascular psychophysiology, decided in 2006 to join research partner Fresco due to their matchable niches of study. Fresco, as director of the Psychopathology and Emotion Regulation Laboratory, has studied the stress-relieving effects of Buddhist meditation for years, and has fit its teachings alongside most of PERL’s research findings in the past. Although the Hughes-Fresco duo had been developing their ideas for a little less than a decade, it was only until this month that they’ve received the funding to test them out.

Even though, Hughes said, there has been “aspirins of stress management therapy” out on the scene for awhile, there is not enough psychological proof that these muscle relaxers actually lower one’s blood pressure. High blood pressure — whether at the effect of genetics or a “dysfunctional family” — is the oft-deadly result of continuous stress. If, Hughes said, they can reverse the influence of stress on blood pressure through mindfulness meditation, then an age-old practice may wind up on the prescription pad in the future.

But for McCarthy, meditation is much more than a mental “pill.”

After founding the Kent Zendo in 1984, and graduating from Kent State, McCarthy pursued his Doctorate in Religious Studies in the following years after. He then studied for years with Roshi Kobun Chino Otagawa at the Jikoji Zen Center in Los Gatos, California, learning the tenets of Zen Buddhism. McCarthy recalls his most enlightening experiences coming from tranquil afternoons on the crest of the Santa Cruz Mountains, memories of a shaved head now covered by stringy, grey hair. He eventually broke ties with Otagawa and drifted back home to Kent, bringing his master’s Soto Zen tradition with him.

As far as teaching mindfulness meditation, McCarthy said that he’s had students in the past come to him with stress-removal in mind, but asserts that there is a “higher” spiritual end that concerns deep personal insight. The same end-goal is found throughout Zen centers in Northeast Ohio, and, as McCarthy reminds us, a state of mind that can be reached by anyone — through whatever method.

Charlotte Silver, a former Kent State psychology major and yoga instructor at Nirvana Yoga in Richfield, said that she digs the “mind-body approach” to her practice. The budding teacher recognizes that Hatha style — yoga with very structured poses — that she instructs can be “distressing” and “just as much as a mental workout as it is a physical one.” Although Hatha, from a Hindu tradition, is not the same practice as the meditation of McCarthy, Silver said that even a “Western-styled, fast-paced” exercise can achieve a similar stress-dispelling effect as something more traditionally Zen.

Ever since Silver took up the practice of yoga five years ago, she was in it for the fitness aspect of the phenomenon. It was her studies in psychology, she said, that opened up a whole new can of curiosity, pairing sweetly her studies and practice.

“It’s all tied together,” Silver said. “If you’re going to be dealing with the mind, then there’s no doubt that [psychology] is useful” to the practice of yoga.

But to solve rising blood pressure?

“Anything can be therapy if you want it to be therapy,” she said.

From Hughes’s perspective, stress is a tricky subject to nail down and define. As far as modern psychology goes, stress is often a result of an instinctive fight-or-flight response to our environment. What’s unique to us is that it’s also totally self-created, and often the result of lingering thoughts, or an idle, wandering mind. The “wear and tear” of both kinds climbs one’s blood pressure, which can lead to health problems like heart disease. The whole goal of Fresco and Hughes’ project, is to “reverse that.”

Both Silver and McCarthy warn that people should not be intimidated by yoga or sitting meditation. At the Upaya Zen Center, for example, McCarthy invites beginners — especially on Monday evenings — to explains the tenets of the Soto tradition over a great mug of green tea. Whether scientifically proven or not, McCarthy, steeped in three decades of practice, suggests that what we call “mindfulness” isn’t as lofty of an achievement as some Zen teachers may make it out to be.

“The thing is that we are always mindful,” he said. “I mean, how would you know that if ‘you’ weren’t there in the first place?”

Deciphering McCarthy’s Zen riddles is another story.

Contact Mark Oprea at [email protected].