Taxpayer money funds gender-biased medical research

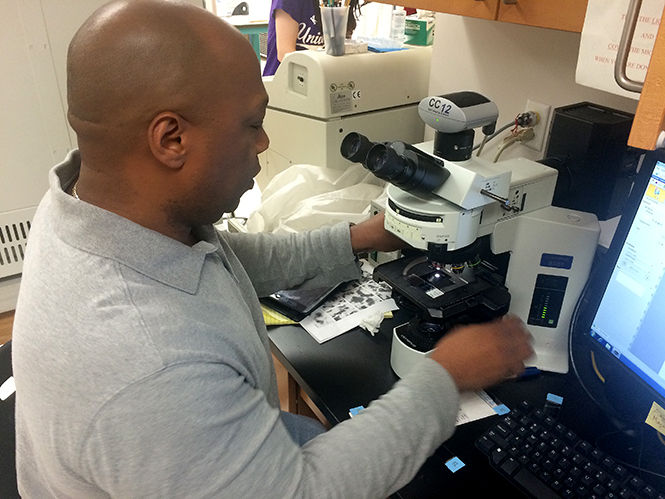

Sean Veney, associate professor of biological sciences at Kent State, examines the differences between a male and female animal model in a Cunningham Hall laboratory.

Tax dollars help pay for many different federally funded industries.

One of them is medical research — a billion-dollar industry that looks for cures and answers to fight serious and fatal diseases.

But the agency that receives the most federal dollars in the medical research industry is fighting a bigger issue.

“The majority of them use male subjects,” said Sean Veney, an associate professor of biological sciences at Kent State. “Which is completely counterintuitive; it’s completely wrong.”

When residents pay their taxes or pick up a prescription at the local pharmacy, those dollars they spend help fund medical research.

In fact, public money helps create billions of dollars in federal grants – as well as awards – at the state level, like those issued by the Ohio Third Frontier. More than $140 billion in federal money was budgeted for research and development in the 2013 fiscal year.

TV2’s Kaitlynn LeBeau explains how a key area of medical research is studying men more than women:

But Veney said a bigger problem exists in this billion-dollar industry: Researchers are leaving out females in their pre-clinical studies.

“Sex matters; sex is a huge factor,” Veney said.

Veney said depression, eating disorders and Alzheimer’s are just a few diseases women are more likely to face than men.

“So just about every mental illness that you can think about has a sex dimorphism – that is, one sex is more likely to contract the disease or suffer more from it,” he said.

Veney’s main research focus is looking at genetic and hormonal factors that regulate the development of sex differences in the brain. He said female animal models are often left out of pre-clinical studies because the gender is difficult to control.

“(The female animal model) introduces so much variability, a lot of investigators for that reason choose to not even think about it,” Veney said. “They kind of put it on the back burner and say, ‘I’m just going to use males,’ but again, that’s a huge problem.”

The variability is in the female hormone cycle, he said. Even if a scientist does use female animals in a pre-clinical trial, Veney said they often remove its ovaries and replace them with a fixed amount of hormones. This only tests the female during one point of her fluctuating cycle.

Male vs. Female Brains

Dr. Sean Veney, associate professor of biological sciences at Kent State, examines animal models to learn how the brain develops differently between males and females. The nucleus in the male animal model (above) is the dark oval shape. It is approximately twice the size of the nucleus in the female model (below.)

Dr. Sean Veney, associate professor of biological sciences at Kent State, examines animal models to learn how the brain develops differently between males and females. The nucleus in the male animal model (above) is the dark oval shape. It is approximately twice the size of the nucleus in the female model (below.)  The nucleus in the female model (above) is the dark oval just to the left of the large dark blue/white shape. The nuclei of the male and female animal models are different in size and therefore develop differently. Veney said studying early development of the brain will answer questions about how humans handle diseases differently, based on gender, later in life.

The nucleus in the female model (above) is the dark oval just to the left of the large dark blue/white shape. The nuclei of the male and female animal models are different in size and therefore develop differently. Veney said studying early development of the brain will answer questions about how humans handle diseases differently, based on gender, later in life.

According to an assessment published in a journal by the National Institutes of Health, the average estrous cycle of a rodent is four to five days, whereas the average menstrual cycle of a human is approximately 28 days. Veney said it is very difficult to have animal samples at every point of a human female’s cycle.

“The problem that happens is when you’re taking the results of experiments you’ve done in a lab that have been only on one sex primarily, and now you’re taking those data and trying to figure out what it’s actually going to do in humans,” he said. “So you’re really not looking at the best results in terms of what that drug or what that treatment’s going to do because you’re only looking at a very fixed time point.”

This issue is often called gender bias. The largest supplier of government grant money for medical research, The National Institutes of Health, is taking a step to get rid of gender bias.

The NIH issued a press release stating it will distribute $10.1 million in grants to 82 institutions for biomedical research. The funds will help researchers expand their studies and include more female representation – this means including more female animals, like mice and cell line.

“The vast majority of the money (NIH) give out comes from tax dollars,” Veney said. “They also have a strong obligation, a strong mission, to make sure that the science from which that money is used for is the most valid it can be.”

This supplemental funding program began in the fiscal year 2013 under leadership of the Office of Research on Women’s Health, according to NIH. Many of the institutions already in the program are universities. One institution is in Ohio – Cincinnati Children’s Hospital.

The initial supplemental funds from the NIH last year totaled $4.6 million, bringing the new total with this year’s available funds to $14.7 million in investments.

Veney said NIH is taking a step in the right direction this year to understand the brain early and find the factors that contribute to diseases later in life – whether you’re male or female.

“The sex of the animal model does matter,” Veney said. “And so in order for the public’s tax dollars to be most utilized, to be put to the best use, I think that that factor has to be in there. I’m very happy to see that NIH is actually finally realizing that.”

Contact Kaitlyn LeBeau at [email protected].