Poetry deepens the sisterly bonds

They resist. They exist. And they have a lot to say about injustice.

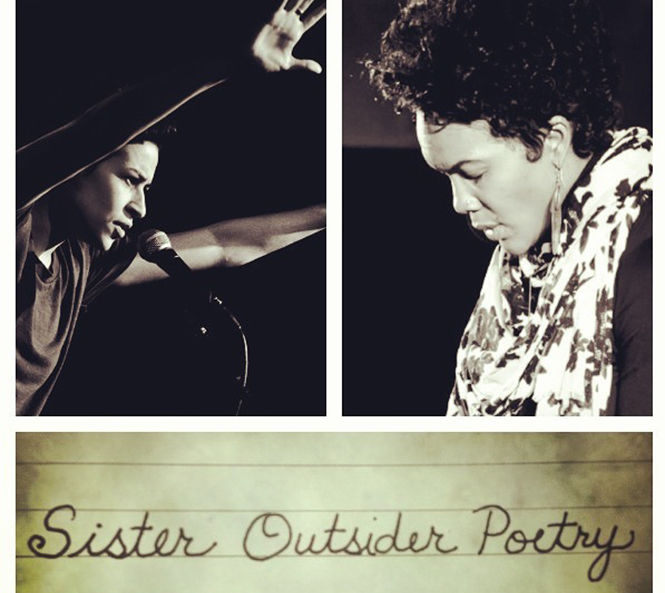

Two of the most popular female performance poets alive can be found in Sister Outsider, a power poetry duo comprised of writer-activists Denice Frohman and Dominique Christina. Both stemming from New York City, the award-winning performers have a track record filled with fire-fueled commentaries on topics ranging from LGBTQ culture to ignorant heterosexuals.

They are continuing their winter tour by stopping at Kent State University this Thursday in the Kiva at 7 p.m. as part of the Guest of Honor University Artist/Lecture Series.

Although the two perform uncannily on stage as a package in near-perfect syncopation, they went almost a decade as singular poets before a partnership crystallized. As solo artists, the two have been named Woman of the World Poetry Slam Champion — Frohman once in 2013, Christina in 2012 and 2014 — and have overlapping careers in education. And both hit stereotypes in a relentless no-holds-bar tone that leaves venues cheering for justice at the end — through somewhat different perspectives. (Frohman is known to tackle sex and gender issues, and Christina, topics of assault and survival).

It was 2013 when the two world-renowned poets came together, transforming from competitors to siblings and bonding through social activism and the writings of essayist Audre Lorde. (Their name comes from a the title of a 1984 Lorde essay on black lesbianism.)

Although Frohman identifies herself as a queer Latina poet, and Christina, a civil rights era-influenced wordsmith, the two appear inseparable when sharing a mic.

“It’s the sisterhood that is powerful, period,” Christina said. “Whenever you have two women come together, there’s always the opportunity for something vibrant to happen.”

The vibrancy from a Sister Outsider performance comes readily from Frohman and Christina’s snap-sassy call and response, paired with their “oh-no-you-didn’t” choreography.

A video of Sister outside’s performance of “Home” depicts the two riffing off experiences of their hometown neighborhoods, first kisses and fleeting romances. The two speak in unison to heighten a certain line’s effect, to agreeing shouts and hell-yeahs from the audience. But that’s typical for an Outsider show.

Despite the shared artistry and zest for activism, the two poets don’t deviate from their distinct upbringings.

While Frohman was entertaining basketball scholarships and mingling with Def Jam Poetry, Christina was pursuing a career as a teacher, along with a brief 1996 stint as an Olympic volleyball player.

Although Frohman was listening to slam by the time she was in college, it took her stage partner until 2011 to delve wholly into the art for which she is now known.

“It took a lot of time to find that particular voice,” Christina said. “But I always had it—it was always mine.”

For Frohman, there is no particular or profound tale of her journey into poethood, which took herself many years before she labeled herself one, feeling that she had to “earn it.” When news aggregator site Upworthy propelled a recording of Frohman’s “Dear Straight People” up past 1 million hits, she became the nation’s undisputed champion of the LGBT-Latino community. The Philadelphia Gay News even listed Frohman as one of the nation’s top gay leaders in 2013.

As far as denouncing false stereotypes, Frohman isn’t a stranger to humor. She labels the solely serious and “sterile” ways of debating social issues as being ineffective, opting for a carefully-crafted monologue instead. Other than shaming homophobia and queer fear, she tackles Latina culture using her upbringing as proof, best represented by the character of her mother in a performance of “Accents” (where chicken, cooking and keychain all “sound the same” in a thick Puerto Rican accent).

“There is no telling my mama to be quiet,” she said with gusto. “Her voice is one size fits all.”

“I like to point out hypocrisies and like to make them sound, and present it, as ridiculous as it is,” Frohman said. “Just like it’s ridiculous for one group to say to the other, ‘You can’t love how you love’.”

Growing up with a strong sense of African-American identity, Christina’s family’s social consciousness (her aunt was one of the Little Rock Nine) never left her as she transitioned into an award-winning poet.

After the death of Florida teen Trayvon Martin in 2012, Christina was invited to read at the Shiloh Baptist Church in Cleveland, Ohio, in front of Martin’s family, along with relatives of Emmett Till, a black child who was brutally murdered by whites in the 1950s. She describes meeting Sybrina Fulton (Trayvon’s mother) as chilling and poignant — as much as an “award” as a performance poet like her can get.

Up to this day, Christina said she is repeatedly reminded of cases like Martin’s, mixed with those of Tamir Rice and Michael Brown, all too often. She often channels multiple experiences of being harassed in front of her own New York City home, along with racial episodes in the national psyche. She said having four children “that look like” boys like Martin and Rice make it all the more real.

“Those are things that are on my mind all the time,” she said. “They sit in my belly and don’t move.”

Both members of Sister Outsider said that it’s this residual distaste left over by those propagators of injustice — those who point out the “otherness” disrespectfully — that ultimately hardens the aim of the sisterhood. It’s through confrontation — using a typical performance of theirs as proof — they said, that sheds a sometimes unpretty light on social absurdities.

Yet there is still the contradiction of the Audre Lorde-inspired name: being simultaneously sisters and outsiders. Coming from poets who “write their ‘otherness,’” it’s this tension, Frohman said, that makes such a partnership in poetry so — as she eloquently puts — “delicious.”

Contact Mark Oprea at [email protected].