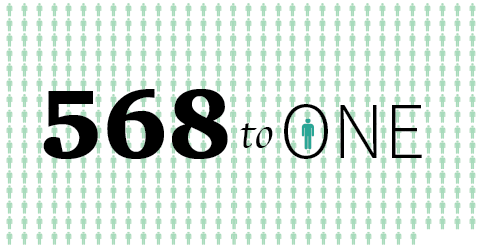

Advisers struggle with limited funds

In the college of Arts and Sciences, the ratio of students to advisers is 568 to one.

Editor’s Note: The ratio of students to advisers in Kent State’s College of Arts and Sciences was incorrectly identified in the graphic on page 1 of the Feb. 3 edition of The Kent Stater. The ratio is 382 students to one adviser, not 568. The 568 number included regional students, which should not have been included. The research department at Kent State is called Institutional Research, not RPIE. The college that works with exploratory students is called University College, not Undergraduate Studies. The graphic that ran on page 1 of the Feb. 3 edition of The Kent Stater incorrectly identified both parties. The National Academic Advising Association set the ideal student-adviser ratio at 300-to-1. The Our View in the Feb. 3 edition of The Kent Stater incorrectly stated Kent State set that ratio.

Lack of availability, unfamiliarity with their students and a constant turnover with personnel—Kent State students have a laundry list of complaints with advisers.

Some colleges at Kent State dealt with limited budgets for their advising staff, according to Steven Antalvari, director of university advising.

“When I went down to do my advising (at Kent campus) I was sent (to Stark campus),” junior political science major Courtney Suder said.

When Suder got in touch with her former adviser, he told her that he was out on medical leave.

“So for a month, I was going back and forth between Stark and the advising downstairs in Bowman (Hall) and got nowhere,” Suder said.

Fortunately for Suder, she ran into a faculty adviser who was able to grant access for her to be able to take classes. But, in some aspects, it was too late.

“I never ended up talking to the undergraduate adviser, so the whole thing seems pointless,” Suder said. “If you are going to mandate that we see an adviser, you need to make sure there are enough to go around.”

Suder said her experience showed a major communication problem that exists with advising.

“The whole thing is backwards and counterproductive because they are going to make people graduate later,” she said. “The classes I need may not be offered every semester”.

Suder is not the only one who has had a bad experience with advising. Angela Graham, a sophomore early childhood education major, had a damaging experience with advising.

Graham planned on changing her major for quite some time to early childhood education, but until she did, she wanted to take classes that would not hurt her chances of graduating in four years.

“The most important thing is graduating in four years,” Graham said.

Like many students, she is paying for her own college, so graduating on time is a must.

Unfortunately, there was a miscommunication with her schedule.

“Three out of the five classes meant nothing,” she said.

Graham struggled to meet with her adviser to work through the anxieties and questions that she had about her new major and what she has to do to be on track.

“(My adviser) was either busy or canceled on me,” she said. “If I wasn’t canceled on and got a chance to talk to her and had her be able to answer some of my questions, I don’t think I would be in the situation.”

Graham thinks there might be more to the problem.

“Last semester, when I spoke with (my adviser) about the issue, I could tell she was overwhelmed,” she said. “She was speeding me through. I was supposed to have a 30 minute block, but it ended up being 10. She seemed stressed and overworked to me.”

Despite her bad experience, Graham still believes required advising is beneficial.

“Honestly, even though there are time restraints, I think (required advising) is important,” Graham said.

However, she emphasized that it has to be meaningful “because I have talked to many people and from what they said, they have been misled in one direction or another. They were just left to think they were fine and then are telling me now they have to add another semester.”

Antalvari said they are actively working to solve some of these problems.

“We know about these issue,” Antalvari said. “And some of these issues have been issues that have been forever. Sometimes it all boils down to resources and money.”

Antalvari said the university’s advising, since its beginning, has been addressing issues of low adviser ratios and what he refers to as the ‘advising bubble’ and have made progress in solving these issue.

University Advising is trying to get the ratios of advisers to students to a level that is ideal for both student and adviser. The National Academic Advising Association has set this ideal ration at 300 students for every one adviser.

Some of the ratios are close to this ideal ratio. The total ratio for Kent State as a whole is at 350 students per one adviser. However, the ratio for the College of Arts and Sciences is almost double the ideal ratio, at 568 students to one adviser.

According to Antalvari, the ‘advising bubble’ is the time where a mass amount of students register and the advisers are most booked up.

“What we are trying to do right now is find out where can we get more registration time” Antalvari said. “The advising bubble will always be there.”

A lot of funding comes from the various colleges for their own advising.

Undergraduate advising, according to Antalvari, is making the most out of what they do have.

“(We’re) trying to utilize the resources we have. And then, when we know we have fully maxed out, (we) say this is the absolute best we can do with the resources we have,” Antalvari said. “We are close, but we are not quite there yet.”

One initiative that the Advising offices are encouraging, is the utilization of faculty advisers. Faculty advisers are faculty members who bring a unique perspective and expertise in the major you are studying to ensure you are being communicated to best information during this advising process.

Antalvari emphasizes that advising is a cooperative endeavor and encourages students to contact his office if they come across any issues or have any questions.

Ben Kindel is a politics coreespondent for The Kent Stater. Contact him at [email protected].