Saban faces Flashes as a ‘James Gang Disciple’

As the final 12 seconds ticked off the game clock in the 2016 College Football Playoff National Championship, O.J. Howard and Derrick Henry lifted an orange, 10-gallon Gatorade cooler high above University of Alabama head coach Nick Saban and doused the back of his crimson windbreaker with the fruit punch flavored thirst quencher.

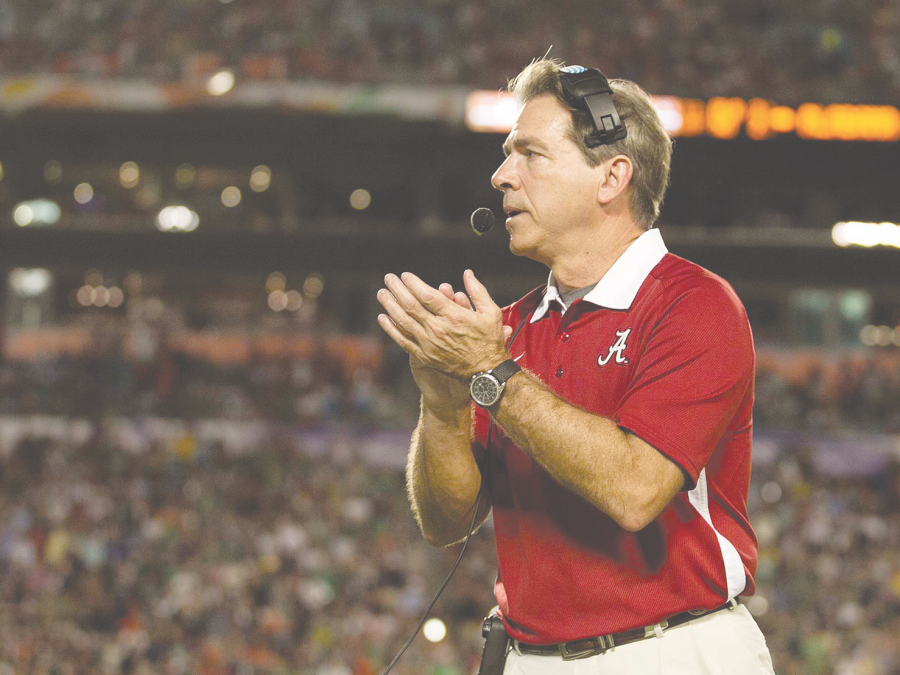

Saban’s trademarked toughness, discipline and meticulous attention to detail had once again catapulted the 64-year-old to the pinnacle of the sport and an unprecedented fourth title in seven years.

But the trek to Tuscaloosa and college football stardom wasn’t without its fair share of stops. There was the one season spent at Syracuse University as the outside linebacker’s coach in 1977. There was the five-year period in East Lansing, where Saban served as Michigan State University’s defensive coordinator under George Perles.

There was the 1990 Mid-American Conference championship when he won in his only season at the University of Toledo, followed by another five-year stint at Michigan State, this time as head coach. There were three separate stints in the NFL. And there was the 2003 BCS National Championship that Saban engineered at Louisiana State University.

Yet, the primary groundwork for his success was assembled 45 years earlier when Kent State Athletic Director Mike Lude hired Don James – the University of Colorado’s defensive coordinator – on a mid-December day in 1970, to lead the football program.

Saban, who was a junior strong safety at the time, became a firm believer in the Don James approach to football, one that emphasized the importance of hard work, organization and self-control.

“Coach James coached from a tower. It was like he was watching all the time. And at the same time, though, you didn’t want to let him down. Therefore, you put forth whatever effort it was,” said Handy Lampley, Saban’s teammate for three seasons. “I would think that (Saban) is probably, without a doubt, a Don James disciple. His basic philosophy of coaching came directly from Don James.”

● ● ●

Lude can’t recall the exact play that ended Saban’s playing career. He knows it occurred late in the 1972 season in a 28-7 road loss to Northern Illinois University. But the details surrounding the precious moment that the 20-year-old went down on Huskie Stadium’s artificial turf are a little fuzzy. What he does vividly remember, however, is the discussion he and James had in the days following the incident.

With four games remaining in the season, James had to figure out a way to keep Saban, a senior, around the program so he could retain his scholarship since there wasn’t a possibility of him rehabbing his injury and returning to the lineup. So, shortly after returning to Kent, James – a native of nearby Massillon – approached Lude with a simple idea.

“What do you think about him being a student coach?” he said.

“Good. We’ll keep him on scholarship and keep him active in football,” Lude said.

When Saban —who also lettered in baseball for Kent State as a shortstop — was later informed of his coach’s decision, he wasn’t given a choice. Rather, he was just told that it was his responsibility to accept his new role with the team.

After the loss to Northern Illinois, Kent State rallied from a 3-4-1 record to win out their three remaining regular season games and clinch the school’s first and only MAC championship.

“I can’t tell you that (the injury triggered his coaching career), but it’s certainly part of the story,” Lude said, who now lives in Tucson, Arizona, with his wife, Rena. “If he hadn’t (gotten hurt), I don’t know what would have happened. No one does.”

It isn’t clear if the fierce competitiveness that Saban helped instill in his teammates sparked the mid-season turnaround, or if the “James Gang” philosophy was simply kick-started into motion following the events of Oct. 28. But whatever the case, James was impressed by what he saw from his student assistant.

Saban had no inclination of making a career out of coaching following his graduation from Kent State in May 1973 with a degree in business. James, on the other hand, wanted to make him a graduate assistant on his staff and sought Lude’s opinion on the matter.

Lude approved the idea, but he still had to convince Saban to accept the offer. Lude ultimately sold him on the notion that it would be a way for him to work toward an advanced degree while staying around the program.

And since Saban’s wife, Terry, was entering her senior year at Kent State, it made sense. Besides, it gave him an opportunity to learn a new dimension of coaching from his mentor, James.

However, after a 7-4 finish in 1974, Joe Kearney – the University of Washington’s athletic director at the time – lured James away from Kent State with the prospect of coaching in the Pac-8. And, as a result, Lude promoted defensive coordinator Denny Fitzgerald to head coach.

Like his predecessor, Fitzgerald wanted Saban to remain on his staff after his graduate assistantship expired and become Kent State’s secondary coach. So, once again, Saban was summoned to Lude’s office in the administration building.

“Nick, if you think you might like to make coaching a career, this would be the greatest opportunity for you — fresh out of college, a full-time staff position as a young college graduate,” Lude told him.

“Yes sir, Mr. Lude,” Saban answered. “I think I would.”

● ● ●

Lampley has been there to support Saban throughout his coaching career. No matter what school or NFL team he has worked for, his former teammate has been by his side. He was at both of his children’s weddings and attends a few Alabama games each year — either the Iron Bowl rivalry against Auburn, the Southeastern Conference title game at the Georgia Dome in Atlanta, or both.

But despite the five national championships, two AP National Coach of the Year awards and seven-figure annual salary, Lampley said Saban has remained the same person he was in college.

“(He was) a good friend off the field. He was the same guy whenever you saw him,” Lampley said.

Ted Bowersox, a Kent State quarterback from 1968-71, remembers Saban as being mature beyond his years — a no-nonsense, defensive guru who would outwork anyone.

“It’s interesting that he has Lane Kiffin calling all the plays. Nick has always been a defensive guy first. That’s his comfort level, and it’s interesting to me that he never transitioned, really, to being a play caller,” said Bowersox, who’s now a State Farm insurance agent in Dana Point, California. “He’s always, to my knowledge, felt much more comfortable on the defensive side of the ball. That’s his expertise.”

When Saban was first given the task of graduate assistant in 1973, no one could have imagined that his coaching career would span five decades and rank him second all-time, behind legendary Alabama coach Paul “Bear” Bryant for most national championships in the modern era.

“I think it’s always a surprise that anybody would go that far in their coaching career,” said Bob Stull, Kent State’s former offensive line coach and the current athletic director at University of Texas at El Paso.

“Certainly he did everything right and successfully to get there,” he said. “You just don’t have any clue when they’re in college. He was always focused and very serious. He was a real tough guy and a solid player.”

For Skip Hall, it’s not hard to envision how and why he is where he is today.

“It’s a great story, there’s no question about that,” said Hall, a former Kent State offensive assistant and member of James’ staff for 18 years. “Coach James surrounded himself with very capable assistants and Nick has done the same thing. That’s enabled him to become as successful as he has.”

Despite the fact that Saban last prowled Kent State 44 years ago, the sense of family that James instilled in the program during the four years he was at Kent State is still evident among former coaches, players and personnel.

Hall has been to two Alabama games in the past few years and received a personal tour of the football facilities from Saban a few years ago.

In March, when Stull made the trip from El Paso to Birmingham, Alabama, for the Conference USA basketball tournament, he made a brief pit stop in Tuscaloosa to visit Saban in-between his offseason preparations, two months after defeating Clemson, 45-40 in the title game.

● ● ●

Shortly after receiving his ceremonial Gatorade shower Jan. 11 — and embracing both players and assistants —Saban darted to midfield at the University of Phoenix Stadium, amidst a sea of crimson joy, orange anguish and gold confetti, to give a short interview to ESPN reporter Tom Rinaldi.

Eleven days earlier, after his team blew out Michigan State, 38-0, in the Cotton Bowl, Rinaldi had asked Saban for a smile. But the tenacious coach refused, citing the fact that there was still another game that needed to be played.

However, when he was probed, this time, Saban agreed, cheerfully grinning to the 23.6 million viewers watching at home on television. It was the same type of euphoric glow that James displayed 24 years earlier after defeating Michigan in the Rose Bowl to clinch his first and only national championship.

And it was proof that the James Gang philosophy hadn’t subsided at the conclusion of the 1992 season when James retired from college football after 41 years.

“Nick still employs, in his program at Alabama today, a lot of the James Gang philosophy,” Hall said. “He’s obviously added a lot of his own personal philosophy to it. But the foundation of what they’re doing at Alabama goes back to the initial Kent State days and the James Gang and the philosophy that we laid down.”

Over the years, James’ original approach to coaching has just been tailored to fit the current landscape of the game by his number one disciple.

And it’s still flourishing.

Nick Buzzelli is a sports reporter, contact him at [email protected].