Students, friends assemble to honor life of former Kent State professor, composer

As snow gently fell outside Cartwright Hall, people meandered past photographs of Halim El-Dabh, hung along the glass windows.

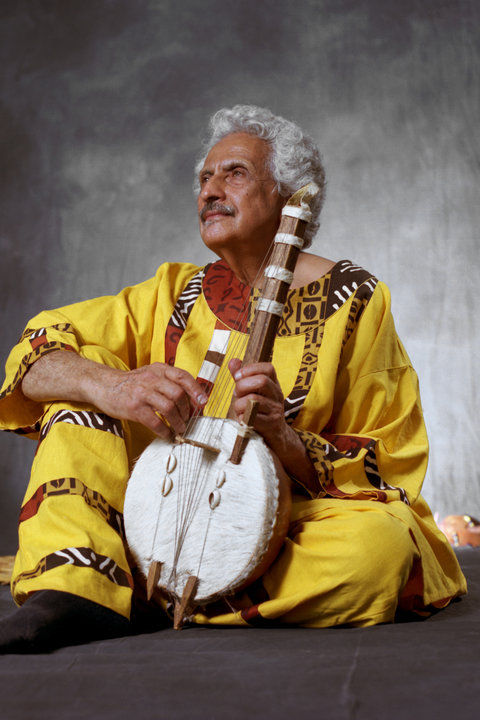

The images portrayed the composer at a young age, with a dog alongside. Standing by pyramids. Older, throwing his arms up in joy. In a portrait shot, his eyes are piercing.

People dressed in colorful garments and clothes gathered Sunday afternoon to celebrate El-Dabh’s life at the “Halim El-Dabh: A Celebration of Life” event.

“I have a gallery and a nonprofit in downtown Kent called Standing Rock Cultural Arts, and I met Halim in the late ’90s, and we became friends and we started celebrating his birthday every year at that gallery starting in the year 2000,” said Jeff Ingram, the executive director of Standing Rock Cultural Arts, who spoke at the event. “He really nurtured the spirit of creativity, just like the mission of Standing Rock Cultural Arts is to nurture the spirit of creativity and really celebrate all of the different works, the artists that are in town.”

El-Dabh, a professor emeritus at Kent State, performer, composer and ethnomusicologist, died Sept. 2 in Kent. He was recognized internationally, and his music hailed in a New York Times article, which described his best known work as a composer of Martha Graham ballets, unlike any other artist.

“For one, he’s written music since the 1940s, and he is one of the recognized premier innovators of electronic music, started writing electronic music before anybody else in 1960,” Ingram said. “His story is really incredible, of people that he met in the ’50s and ’60s, and then he landed at Kent State in 1968 and fell in love with the area. … His compositions range from really noisy, cacophonous to really beautiful, melodic, and he brings all the knowledge of ancient Egypt with him.”

The musical pieces of El Dabh that were performed at the celebration featured cello, drums, piano, derabucca, voice and more. The opening number, “It is Dark and Damp On the Front,” played on the piano by Tuyen Tonnu, was haunting, the notes chasing each other to tense crescendos.

“Halim’s work is unique because he was a pioneer in his style,” said Leatrice Tolls, a community member who helped event organizer Mark Wiitanen. “He defined his work. It wasn’t brought about by anybody; it was built upon ancient tomes, things that came through him spiritually and things that, for him, honored the land and people’s highest potential.”

Tolls said she met El-Dabh as a 17-year-old at Kent State and had been friends with him ever since.

“As an educator in a university, he wasn’t stuffy, ever,” she said. “He demanded excellence of people, but only by them honoring themselves, and you could feel that when you’re with him and when he challenged you, or just when he smiled at you. He had an amazing, amazing way of just looking at you, and you just were present with him, and you felt like yourself.”

Along with several musical performances of El-Dabh’s work, the event included a poem, audio documentary “The Sound of the Soul,” prayers, hymns and remarks from those such as John Crawford-Spinelli, the dean of the College of the Arts; Kazadi wa Mukuna, a professor of ethnomusicology; Deborah El-Dabh, the wife of El-Dabh; and Beverly Warren, the president of Kent State.

“We will pause today to celebrate, to appreciate and to reflect on the influence of one of Kent State’s, and the world’s, most iconic composers and scholars of musicology,” Warren said, standing at the podium. “I was impressed by his grace and his strength, his vitality and his vibrancy. I had a brief glimpse into this larger-than-life personality that has touched so many lives over the years, and I can certainly tell you he touched my life on that wonderful evening.”

A group of drummers and musicians took the stage to perform El-Dabh’s “Symphony for 1,000 Drums.” The audience was encouraged to participate, to leave their seats and join in dancing and playing.

Slowly, while the beat of the rhythm vibrated through the room, they danced, the group at the foot of the stage growing until it nearly outnumbered those sitting, the people a blur of colors and moving limbs as the beat intensified toward the crashing of a gong. When it was finally over, they cheered.

“More and more, I became music,” El-Dabh said, narrating the audio documentary, his voice sonorous through the speakers. “Music bringing crowds of people and neighbors together — interacting, engaging and resonating for perpetual festivities. Essence of waves, waves of people in an ebb and flow of nations and countries called to a state of conscious wariness that music is life, and life is music.”

Cameron Gorman is a features correspondent. Contact her at [email protected].