A son’s sudden death opens a mother’s eyes to the raging heroin crisis

It was a typical Saturday in August 2015 when Anna Zsinko pulled into her driveway in Streetsboro. The sun glistened, warming her skin. She, a neighbor and a friend visiting from Florida had been out shopping and eating lunch.

But something didn’t seem right.

The garage door was closed; her 33-year-old son Matt, who lived in the basement, left it open when he was home. Inside, the kitchen counters were clean; Matt always left a mess.

Matt couldn’t be asleep, she thought, not at 4 p.m.

Anna turned to her friends, afraid.

“Something’s wrong, something’s wrong, something’s wrong with Matt,” she said, frantic.

The Trouble with Matt

As early as third and fourth grade, Anna says Matt had trouble paying attention in school. His grades were never good.

In middle school, he struggled with low self-esteem and lack of confidence. Matt had symptoms of what was later diagnosed as ADHD, like nervous tics and twitches. He could never concentrate in school, and peers made fun of him.

As he grew older, Matt called his mind a “pinball machine.” His thoughts bounced around, smacking into each other, whirling up and down, swirling left to right.

No matter how hard he tried, Matt could never score high in that colorful, twisted game.

“His mind raced probably a thousand miles an hour to get the thoughts out of his head, out of his mouth,” Anna said. “He spoke extremely, extremely fast — intelligent in so many ways, but he struggled to get his thoughts straight.”

Sometimes, the glass protecting his fragile world would shatter. There was no “Out of Order” sign to warn him. He could get so frustrated that he would punch a hole in the wall of his bedroom.

As he grew into a teenager, his rage festered. Matt joined his friends in experimenting with alcohol, then marijuana. He dabbled in other drugs, too, though Anna doesn’t know the details. High school friend Jess Easterling said they were into psychedelics like acid when Matt was a senior, later using meth a few times together in their 20s.

Despite Matt’s emotional problems, Jess says he was “kind to a fault.” Once, she remembers, her car ran out of gas, and Matt assured her not to worry, then walked several miles to a service station.

Anna remembers instances when Matt was late to work or would call in sick because he was too busy doing favors for others.

Sometimes, his kindness let people take advantage of him, Jess said. They’d ask for too many rides and would sometimes sell him fake drugs.

“Matt would give the shirt that he didn’t have off his back,” Anna said. “He would loan people money. … And then, who do you think he went to when he didn’t have the money? Me.”

Sometimes he’d call her selfish, and she’d reply, “You know, Matt, I’m not selfish, but if you didn’t live at home and you had to pay bills, you couldn’t do this.”

Matt Searches for Matt

Matt tried college after he graduated from Kent Roosevelt High School. He took classes at Cuyahoga Community College and Kent State Stark. He always carried paper and a pencil, journaling through life, even delving into poetry.

Matt couldn’t turn his writing into a job, though, and he never finished school. He worked mostly in places like Taco Bell and The Brown Derby Roadhouse, and a production job at a metal-stamping company.

Beginning at about age 23, Matt visited with a neurologist, then three psychiatrists — bipolar disorder, they said, and prescribed various medications.

Anna encouraged Matt to seek counseling. He did for a while at Coleman Professional Services in Ravenna, but like everything else, it didn’t stick.

Doctors and his mother warned him drugs for emotional and mental disorders took time to begin working, but Matt’s impatience became a monster. He wanted nothing more than to get better, and he wanted it now.

After two days, he’d say to his mother, “They’re not working, they’re not working.”

So He Medicates

Matt swallowed pills, and they swallowed him back.

He took Adderall for his ADHD, mood stabilizers for his bipolar tendencies, Xanax for anxiety and panic attacks. Anna was pretty sure he took too much Xanax. Doctors kept prescribing, and Matt kept abusing.

Anna now knows in the few years before his death, Matt abused Vicodin and Percocet, too.

Matt scoured the internet reading about drugs and disorders, and he even diagnosed himself with mania at one point.

“He would call me and say, ‘Mom, look at this!’” reading symptoms off his laptop, Anna said. “‘This is me.’”

Matt could never find a peace of mind — staying up until “4 or 5 in the morning because he couldn’t get his mind to settle down.”

A Connection with Kids

Friends around Matt were getting married and starting a family — but not him. He was always the babysitter, the uncle. Anna said he loved kids and knew how to get down on their level to play with them.

He just had that spark around little ones, Anna said, and he wanted his own kids “to have the life he didn’t have so they didn’t have to go through what he had to go through.”

A close friend even asked Matt to be the godfather of her little girl. He said no because he was too anxious to take on the responsibility.

Anna believes Matt was beginning to feel ashamed about living at home at 33. He talked about wanting to reconnect with Amy, a girlfriend from his past, and starting to build a new life, but “something always held him back from achieving things.”

“I feel all these people that we’ve lost don’t want to be addicted, want connection with family and friends, want jobs, want to feel that they’re leading a good life,” Anna said. “And for whatever the reasons are, it doesn’t happen for them.”

When Matt died, they found his wallet — full of crayon drawings and pictures of his friends’ kids.

Hijacked by Heroin

Editor’s Note: “Tina” is an alias to protect the source.

Matt’s heroin use began about the time he met Tina in late December 2014 or early January 2015, according to his journals. Anna remembers sitting with her son at the kitchen table five months later as he told her about the relationship. It was as if she was the next girl he was swooping in to rescue, Anna thought.

“Matt had this thing about saving girls,” she said with a smile. “He just had a soft spot for girls, you know? And part of that was I always said, ‘Be good to girls.’”

He told his mother that he and Tina could support each other on their road to sobriety. The word “heroin” was never uttered. Anna hadn’t even heard of fentanyl, a drug about 50 times more potent than heroin, before the toxicology report came back detailing how his last dose was laced with it.

Looking back, Anna wishes she would have reacted differently. Instead of giving him a nod of approval, she said she should have listened closer; maybe, she wonders, the conversation was Matt’s way of communicating to her the depth of his drug dependence.

Tina went to jail on drug charges that June. In August, she wrote a letter to Matt, talking about her desire to get out and rebuild her relationship with her children (by an earlier relationship). Tina marveled over his many wonderful traits, and she said she didn’t know what she’d do if anything ever happened to him.

Anna opened the letter. Tina didn’t know, but Matt was dead.

First High, Best High

Matt’s first experience with heroin came when he snorted — “high on a level he’d never seen before,” Anna said, gathering from his journals.

He wrote that the real start of the addiction didn’t arise until his first injection in February. The warm feeling of euphoria overtook his body, and he was hooked.

It’s the best high in the world, and nothing other compares to it — that’s what makes it the worst, he wrote.

Pens and Needles

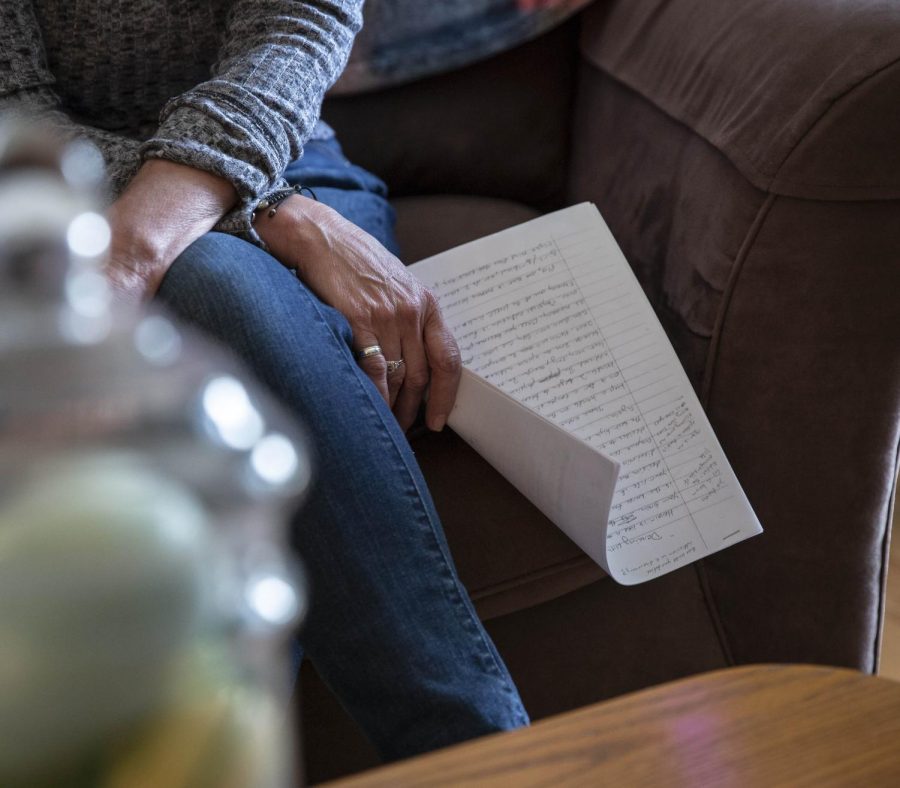

Matt was always writing. He penned himself an escape when the world got too chaotic. Every journal entry showed him sinking deeper, revealed how troubled he was.

Anna didn’t understand the intensity of his despair until she sat down to read his words after his death.

On Aug. 17, he wrote:

I’ll never touch heroin ever again. I really shouldn’t touch pills again, either. I spent six months on heroin, and it cost me a lot more than just a lot of money. It’s the hardest drug to get off, as well as the hardest one to stop doing. It’s the hardest one to get off because of the psychological and physical addiction. It’s the hardest to stop doing because it’s so good.

…

Heroin is like a terrorist in the sense that it hijacks your brain. It really is the worst in the world. It’ll ruin your life if you allow it to. It’s the worst decision that anyone could ever make. Heroin does not discriminate. It does not care who you are and anyone can fall victim to it.

Anna wishes she could see the words “rehab” or “treatment” as she read his thoughts unfold on paper.

A Disorder Too Big

Matt’s father, John, had been telling their family doctor about Matt and the issues plaguing him and how he wasn’t improving. The doctor had some experience treating patients with mental illness issues like Matt’s and offered to meet him.

Matt visited the doctor two days before he died. They talked for 45 minutes. Afterward, Matt told his mother the doctor couldn’t mend him. His condition was too severe and beyond his skill, the doctor had said.

“I’m not sure what he was suffering from,” Anna said. “At the time, we didn’t realize Matt was suffering from a dual diagnosis — addiction and mental illness.

“I think one feeds the other. … It’s just this cycle, and now I’m wondering what was happening.”

Anna wonders whether that appointment made Matt feel even more hopeless.

The doctor did write a prescription, but Matt didn’t live long enough to fill it.

Football Friday, One Last Time

Matt hid his addiction well. Anna says he was healthy-looking with tan skin, and he acted pretty normal when he was out and about, often bubbly and joking around.

The last evening of his life, Matt headed to a Streetsboro High School football game with Amy. They had remained friends after their relationship didn’t work out, but he always loved her, Anna says.

Matt returned home after the game and raided the refrigerator. He asked John for $20; he was out of work at the time. Of course, his father gave it to him.

Anna and John went to bed. That was the last time they saw their son.

That next afternoon in the kitchen, Anna sent her friends to the basement. His room was locked. They pounded on the door. They yelled his name. They heard nothing.

Anna went outside to call 911. Minutes later, John and a police officer patrolling the area arrived almost at the same time, Anna still on the phone.

John stormed downstairs and kicked Matt’s door open. In front of him was what no parent ever hopes to see.

Matt. Dead. A needle by his side. Blood stains on the carpet.

Overdose. Heroin.

The friend came upstairs and told Anna that her son was gone.

Anna’s mind spun. Matt self-medicated with pills before to moderate his bipolar disorder, but heroin? This was the first she’d heard of it.

Between tears and shock, each taking its rotation, she finally spoke to the officer.

“I want to go down there,” she told him.

“I don’t think you should,” she remembers the officer saying. “I just don’t think you should.”

Rest in Peace

Matt’s life was celebrated at a memorial service the next Thursday. It was mostly family and friends.

But a girl Anna didn’t recognize asked if she could add a eulogy.

It was Jess, whom Anna hadn’t seen since high school.

She stood up to speak, her eyes overflowing oceans with the clearest, bluest truth. Matt was the fourth or fifth friend she’d lost to the heroin epidemic.

Jess’s hair is choppy and lilac-colored, her laugh boisterous and her personality too colorful for the world. Here’s what Jess remembers saying:

When I was about 19, I struggled with substance abuse. I had no place to stay. I wasn’t welcome home at the time. I had lost my job. Matt would sneak me into his house to sleep in the morning after his mom went to work. He would go sleep on the couch so I could have a bed.

One day, I was looking for a job. We were in the Chapel Hill area. I was putting in applications, and I saw this dress. It was at one of those discount stores, and it was only $14. We were broke, you know what I mean? I would routinely run out of gas. That’s how broke I was.

He maybe had $20 to his name, and that was the rest of his money for the week. I was trying on clothes, filling out applications, you know. We were kicking it together. And he said, “Oh, that dress looks really good on you.”

And I was like, “Yeah. Once I get a job, I’ll get it.” I went to try on more stuff, and once I came out, he had bought me the dress.

He would give the shirt off his own back. He was that kind of guy. … He knew that I was struggling, and he lifted my spirit. He just had this heart that was too big.

Jess said she wore that dress all summer.

Anna and the rest of the audience were reduced to a puddle. That was the sweet, selfless son she had nurtured.

How was it that she, the parent, was burying him?

Even today, almost three years after Matt’s death, Anna can’t resolve what she calls a “deep-down sorrow.”

“I don’t know that I’ll ever feel accomplished or good about anything I’ve done,” Anna said. “As a parent, your biggest achievement in life is raising your kids and having them healthy and happy, and having a good relationship. … Nothing I do or will ever do will ever mean what that could have meant to me.”

Love Kills

Anna is still shaken by how quickly Matt died. Looking back, she realizes there were signs.

Matt was always working, but he never had money. He would ask, and Anna would give. Anna just thought he was poor with managing his finances.

When Matt told his mother about Tina, he talked about getting sober. They could be each others’ crutch through recovery. But as time went on, Matt’s behavior was more erratic; nervous tremors would rock his body, and he even bit his hands and arms. In June, he came to Anna:

“I need to go to a halfway house,” he told her. “I’ve gotta get out of here.”

Anna never heard Matt say the words “opioids” or “heroin.” She didn’t realize the extent of his addiction. She thought he wanted to rid himself of his unhealthy lifestyle choices and end his self-medicating with pills.

Anna called Root House, a residential facility in Ravenna for recovering male addicts. They said he needed to go through detox first. Matt blew it off, claiming he didn’t need that. Anna phoned other places, but there was always an issue — sometimes lack of beds but most often because they wouldn’t accept Medicaid. Matt never made it to a recovery facility.

Two days before his overdose, Matt was “vomiting his guts out,” Anna recalls. She had no idea he was in withdrawal. He was dope sick.

After the death, she found torn Q-tip buds in the bathroom. Addicts, she has since learned, use them to filter heroin liquid when filling their needles.

A Mother’s Regrets

Anna now realizes she was enabling her son. She had supported him — too much — his whole life, providing a safe roof to live under and helping pay his bills when he needed it.

There’s a difference between enabling and loving your child, she said.

“And I think I loved Matt to death,” she said, shaking her head slowly, her eyes glassy with a film of tears.

The grief of losing Matt crashes in waves. Sometimes Anna imagines she can hear her son’s voice.

“I know he would tell me how much he loves me,” Anna said. “He would tell me he’s sorry he’s causing me pain. And maybe, I hope and believe, he would tell me that he’s fine … because he did that so much in life.

“When he was having one of his bipolar rages and knocking holes in the wall, after he’d calm down, he’d tell me he’s sorry. And I would tell him the same thing — that I love him, and that I’m sorry. I’m sorry that I didn’t listen to him when I think he tried to talk to me.”

A New Life for Anna

About a week after Matt’s death, Anna reached out to Jess on Facebook, thanking her for her words at the memorial.

Jess messaged Anna back, suggesting she check out OhioCAN, a statewide organization for family members affected by addiction. Anna joined and now serves as treasurer for the state and is active in Portage County.

The group organizes community events to raise awareness and education on addiction, and it looks into recovery and treatment programs for addicts. But most important, Anna says, it focuses on family.

“It’s amazing how many people of all walks of life have had this happen to their families,” Anna said. “All the change that’s happening in this country right now is because of the families; these are grassroots organizations — people who have lost their family, their kids, their nieces or nephews, their brothers or sisters, even parents — fighting for change.”

Anna says that when the worst happens, a heart can shrivel up and lose itself to the world.

But Anna’s heart broke open, and she found a new purpose.

Right now, she has piles of strangers’ shoes, labeled by name and date of death, sitting in what used to be Matt’s room. She’s preparing them for a “Steps for Change” event in May, where families gather to honor loved ones they’ve lost to addiction.

“We say, ‘If you go somewhere and one person heard you, it was worth your time,’” Anna said about group members she meets with every two weeks. “If you just, you know, got to one person, you had a good day.”

Anna’s faith has always been an important part of her life, even more now after Matt died. No two people grieve the same, she says, and it’s a process she’s had to learn to do on her own, especially as more time passes. Year two after Matt’s death was harder than the first year, she says.

“I think as more time goes on, it really settles in that you’re not going to see them again,” she said, and paused for a long moment. “I think that my faith is helping. I think Matt’s helping me. I feel like, you know, he wants me to be OK.”

But there are days when it all comes flooding back.

“I can go somewhere and have fun, honestly, but I get in that car and I drive home and I start crying again,” she said through tears. “Sometimes I think I have to get off Facebook because I see everybody’s kids and marriages and grandkids and all this good stuff. … It’s not that I begrudge them of their happiness; it’s just I don’t feel that way, and I never will.

“I still cry every day, to some extent,” Anna said, “but I’ve grown as a person and through life experiences. I think I’ve grown an incredible amount, and I think I have a deeper heart. I feel good about that; I feel bad about how I had to grow.”

Valerie Royzman is an administration reporter. Contact her at [email protected].