KSU anticipates decline in enrollment this fall

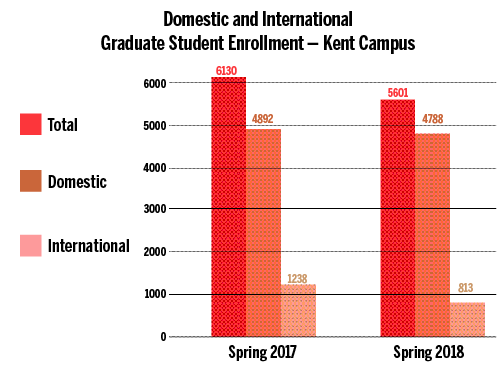

Domestic and international graduate student enrollment

Kent State is expecting a 2 percent dip in enrollment this fall, which could mean a loss of anywhere from 300 to 600 students, said Kristin Anderson, the director of external media relations.

The university will have a clearer picture of the numbers once classes begin, she said.

“When we are dealing with 40,000-plus students, the numbers do fluctuate as students transfer in and out, make last-minute decisions, change majors, lose and gain financing — you name it,” Anderson said.

The university isn’t alone in feeling the sting of having fewer students on campus. Undergraduate enrollment in the U.S. is down for the sixth straight year.

According to data from the National Student Clearinghouse Research Center, a nonprofit education organization, Spring 2018 undergraduate enrollment dropped more than 275,000 students, or 1.8 percent, compared to the previous spring.

The center reported enrollment was down in 34 states this year, with Ohio landing in the top 10 largest declines.

At Kent State, university officials attribute the enrollment slump to two major factors. One is students who successfully graduate in three years because they began at Kent State with credits earned through the College Credit Plus program, Anderson said. The other — in line with trends universities are experiencing nationwide — is a decline in international students.

Despite fewer high schoolers graduating and pursuing a college education, which ties back to the 2008 recession when parents were having fewer children, Kent State isn’t counting on the enrollment drop to come from freshmen.

In fact, the university set an “all-time record” for admitted students at the main campus, said T. David Garcia, the senior associate vice president of strategic enrollment management.

As of July 8, the university was awaiting 13,829 freshmen at the main campus. Garcia said he doesn’t foresee reaching 14,000 before the semester begins.

Compared to previous years, Garcia said he noticed a “slow start” as students began submitting applications.

“We were down about 1,400 applications from last year at the same point in time,” he said, “but because of that slow start, we really put a lot of emphasis on getting students who started an application to complete it.”

He added the university’s latest recruitment efforts and “doubling down on outreach more so than last year” contributed to more admissions.

“We have, in collaboration with University Communication and Marketing offices, created more outreach efforts to students and parents,” he said. “I think the biggest change was we added social media to our efforts. That’s more or less where high-schoolers are at; they’re on social media.”

As the fall semester inches closer, Garcia said the university is seeing a decrease in applications submitted by transfer students who attend a four-year public or private university. On the flip side, the number of applications from transfer students who are attending a two-year community college is increasing.

Garcia predicts transfer enrollment will be flat by the start of Fall 2018, which he considers a success.

He said probably in the past three years, international enrollment used to bring in about 90 to 100 students that counted in transfer numbers, “but that number has really dwindled down to probably less than 25.”

Open Doors, an annual study on international enrollment conducted by the Institute of International Education, reported in November that the number of new international students — meaning those enrolled at a U.S. institution for the first time in Fall 2016 — fell 3.3 percent in 2016-17.

According to enrollment tracking data provided by Kent State, close to 1,800 international students were enrolled at the main campus last spring — but that number is about 670 faces fewer compared to the spring before.

“Because we had 3,000 international students (two years ago), the hit that everyone’s taken — Kent State is going to feel it more because we had more of those students enrolled” compared to other Ohio universities, Garcia said.

The international graduate student population took the biggest punch. Between Spring 2017 and Spring 2018, the university lost 425 students in that category alone.

During that same period, of the 12 colleges at Kent State, all but three — the College of Nursing, the College of Public Health and the College of Business Administration — saw a decline in domestic graduate students.

International graduate enrollment mirrored these trends, with the exception of modest increases in the College of the Arts, the College of Public Health and the College of Podiatric Medicine.

“And at the moment, it’s not getting any better,” said Marcello Fantoni, the associate provost of Global Education. “There are many moving pieces in this picture.”

Beginning in 2016, the international population nationwide began to flatten due to a number of circumstances, including the growing appeal of universities overseas along with a dramatic increase in visa rejections.

At Kent State — what Fantoni calls a “little United Nations with people from over 100 countries” — the Office of Global Education witnessed many Indian students encounter visa denials, and it’s likely that some of them chose other competitive countries to apply to.

Fantoni said the Trump administration’s attitude toward immigration plays an “enormous” role in the dwindling international enrollment numbers.

“We all know with the current administration, the perception of this country around the world is no longer as a welcoming place,” Fantoni said. “That is not because of the executive orders, per se, … but because of the echo in the media. It had an enormous impact on the public opinion and perception of this country around the world.”

Though many are quick to blast President Donald Trump’s policies in the midst of this international enrollment hardship, Fantoni said “even if the administration’s stance is a problem, the other reasons still exist,” and some began before Trump took office, like visa rejections.

“You know, the king of Saudi Arabia died, and that has nothing to do with the current administration — but definitely, it’s making it worse.”

Most recently, the State Department has been restricting visas for Chinese graduate students. Since June 11, the administration reversed an Obama-era policy allowing Chinese citizens to secure five-year student visas; now, the duration of the visa will be one year, with the chance to reapply annually.

As the international crowd continues to wane, Fantoni said the Office of Global Education has been tasked with “rethinking the model for international students,” which has led to new programs. Because of their success so far, he said this fall is looking “more contained than we projected and feared.”

The American Academy in Brazil — a partnership between Kent State and the Pontifical Catholic University of Paraná that allows Brazilian students to take Kent Core classes taught in English by Kent State faculty at their PUCPR Curitiba Campus — launched its first cohort in July and already has 16 students enrolled.

Fantoni said this “international micro-campus,” is setting the stage for a good comeback year.

Between 2017 and 2018, there were 129 international non degree students — like shorter-term English as a second language students or those involved with a teacher training program — who attended a variety of programs on campus.

Although he can only speak for his department, Fantoni said the university seems to be working hard to create conditions for enrollment to begin growing next year.

“2017, 2018 will be recorded as terrible years for international enrollment,” he admits, “but we’ll get back in 2019.”

Valerie Royzman is the features editor at [email protected].