Former Kent State football player overcomes drug addiction

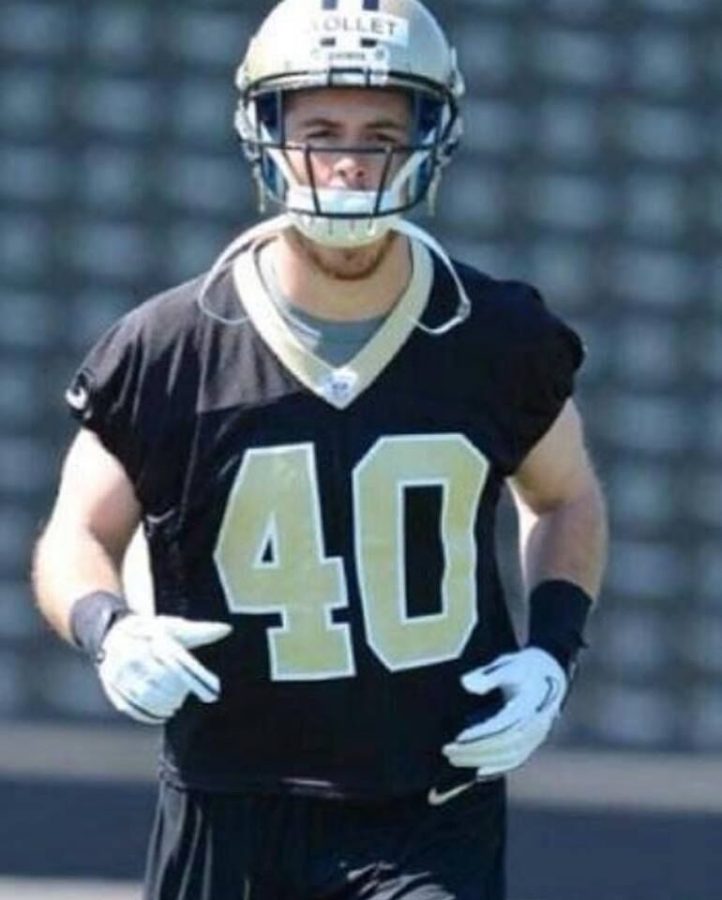

Former Kent State football player Luke Wollet went from NFL hopeful to addict within a short period of time.

Wollet, a 26-year-old Youngstown native, knows exactly what it’s like to have dreams right in front of you and watch them slip away.

“My dreams of playing in the NFL turned to my dream of just chasing drugs,” Wollet said. “I really didn’t care about football as much anymore. My dreams essentially turned into my nightmare.”

Wollet started out as a star football player at Kent State. He played 10 games his freshman year and started all 12 games during his sophomore year, which is when he suffered an injury.

“I broke my ankle my sophomore year, and it was the first time I was exposed to pain medication,” Wollet said. “I took it as prescribed, and it wasn’t an issue. I still had sports in my life, and I didn’t have a lot of anxiety or depression that came with the following years and into my senior season.”

During his senior year, Wollet tore his left MCL, causing him to fall back on painkillers prescribed by a doctor.

But it didn’t stop there.

Once the medication stopped, Wollet found himself searching for more. He went to the streets, which led him to heroin, the drug that gave him the closest effect to his original medication.

During his injury, Wollet experienced high levels of anxiety and stress with his upcoming future in football. He dreamed about taking his career to the professional level. Wollet was invited to a training camp by the New Orleans Saints in 2014 after going undrafted.

He was so close to what he had worked for all his life.

That dream was cut short. Heroin had taken over, and Wollet was too far gone into the world of addiction.

“For a few years, I really tried fighting the battle on my own,” Wollet said. “I was living in Cincinnati, and my father drove down from Youngstown. He didn’t really know what was going on, but he said he felt the tug on his heart, and he offered me help.”

His family wasn’t sure what they were walking into, but they came with all the help they could give. Wollet’s perceptions of “being a man” clouded his views on getting sober.

“We live in a society where, especially myself, the perception of being a man is very wrong,” Wollet said. “I thought, ‘I got myself into this problem I need to get myself out.’ But when someone offered me help, it changed my life. I was going to die as an addict.”

During his addiction, Wollet lost 30 to 40 pounds and underwent some physical changes. He believes his addiction caused a greater mental toll than it did physically.

“As someone who was looked at as a coveted athlete and who was going to be successful, I didn’t want to live anymore,” Wollet said. “I planned my death. Suicide was days away. It’s not less than that.”

Family and God played a large role in Wollet’s path to sobriety. He credits his faith for opening doors for him and giving him the opportunity for his current job. Wollet works as a national outreach representative for Banyan Treatment Center in Pompano Beach, Florida.

“My job includes intervention and sharing my story to help families that are carrying a lot of guilt and shame so that they know they’re not alone,” Wollet said. “I try to do some work on changing the stigma, and the biggest thing I do in my job is connecting people to help.”

His coworkers describe him as a “beacon of hope in a journey that, to most, seems dark and hopeless.” Wollet seems to have touched lives beyond just his clients.

Wollet has been sober for over two years, but he counts the time from his last gamble. Alongside drugs and alcohol, gambling also played a role in Wollet’s addiction.

“I know I’m still early in this journey myself,” Wollet said. “But amazing doors have opened up in a short time, and I just want people to know there’s a better life for them and help is available.”

Wollet uses his mindset through his job to help others struggling with addiction. His advice and abundance of hope is something he passes on to people of all ages struggling in the same ways he did. Wollet often deals with families who are asking themselves, “What did I do wrong?” But he believes this question isn’t the most important to focus on.

“The most important is getting that person help,” Wollet said. “So I think until we, as a society, can all come together and have these discussions and support groups and some real change, this problem is going to keep getting worse.”

Wollet believes college students between the ages of 18 and 22 are at the prime age to fall into addiction. Little things such as a few innocent nights of partying instead of dealing with a personal problem can snowball into a larger issue.

Although he hoped that his purpose in life would be to play football, Wollet now believes his purpose is to tell his story.

“You’re not alone in this journey,” Wollet said. “There’s only one way this works: death or recovery. Or jail or recovery. There is a better life though.”

Lexi Marco is the health reporter. Contact her at [email protected].