(CNN) — The Supreme Court’s conservative majority on Tuesday signaled it will require schools to provide opt-outs for parents who have religious objections to LGBTQ+ books read in elementary schools, an outcome that would continue the court’s years-long push to expand religious rights.

During more than two hours of feisty oral arguments in a high-profile case involving a suburban Washington, DC, school district, the court’s six conservatives appeared to be aligned on the idea that the decision to decline opt-outs for books burdened the rights of religious parents.

“It has a clear moral message,” Justice Samuel Alito, a member of the court’s conservative wing, said during a spirited exchange with liberal Justice Sonia Sotomayor.

“It may be a good message,” Alito added. “It’s just a message that a lot of religious people disagree with.”

The court’s liberal justices repeatedly pressed the idea that simply exposing students to ideas in a book could not possibly burden religion. A majority of the court seemed to suggest in a 2022 decision that mere exposure to ideas doesn’t amount to a coercion of religious beliefs.

“Looking at two men getting married – is that the religious objection?” Sotomayor pressed the attorney for the parents who challenged the books. “The most they’re doing is holding hands.”

But others on the court seemed to be open to finding a way to side with the religious parents without finding “coercion” took place.

Several of the key conservative justices in the middle of the court asked questions suggesting they are concerned about the approach taken by the Montgomery County Public Schools in Maryland. After all, some of them noted, state law already requires its schools to opt students out of sex education if requested.

“As far as simply looking at something, looking at the image of Muhammad is a serious matter for someone who follows that religion, right?” Chief Justice John Roberts asked in a question geared at disputing the argument that looking at material can’t burden religion.

Justice Brett Kavanaugh at one point appeared to be scolding the schools’ position, noting that the state of Maryland was founded on “religious tolerance, a haven for Catholics escaping persecution in England.”

“I guess I’m surprised,” Kavanaugh told the lawyer representing the schools, “this is the hill we’re going to die on in terms of not respecting religious liberty, given that history.”

‘Can I finish, please?’

The arguments – which came toward the end of a Supreme Court session that has become increasingly defined by legal challenges involving President Donald Trump – at times seemed especially tense. At one point, Sotomayor attempted to interject as Alito was speaking about one of the books involved in the dispute.

“Wait a minute,” Sotomayor jumped in.

“Can I finish, please?” Alito fired back.

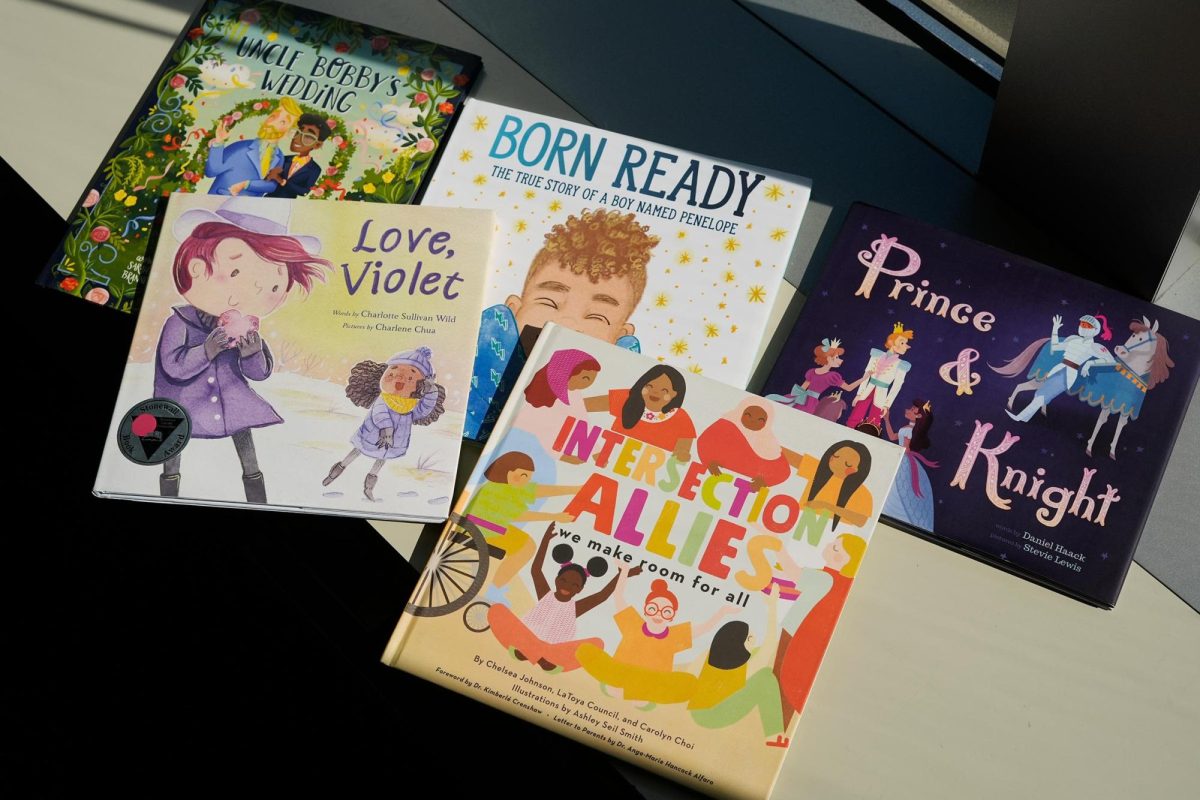

As part of its English curriculum, Montgomery County approved a handful of books in 2022 at issue in the case. One, “Prince & Knight,” tells the story of a prince who does not want to marry any of the princesses in his realm. After teaming up with a knight to slay a dragon, the two fall in love, “filling the king and queen with joy,” according to the school’s summary.

Another book, “Born Ready,” tells the story of Penelope, a character who likes skateboarding and wearing baggy jeans. When Penelope tells his mother that he is a boy, he is accepted. When Penelope’s brother questions his gender identity, their mother hugs both children and whispers, “Not everything needs to make sense. This is about love.”

Some of the justices appeared to be taken aback by the content. At one point, the attorney for the schools was explaining one of the books – which has since been removed from the curriculum – when Justice Neil Gorsuch jumped in. Gorsuch and several of his colleagues indicated they had read the books.

“That’s the one where they are supposed to look for the leather and things – and bondage, things like that,” Gorsuch said.

“It’s not bondage,” the schools attorney, Alan Schoenfeld, interjected.

“Sex worker, right?” Gorsuch said.

“No,” Schoenfeld said.

“Drag queen?” Gorsuch continued, after being reminded of the part of the book at issue by his neighbor on the bench, Justice Amy Coney Barrett.

“The leather that they’re pointing to is a woman in a leather jacket,” Schoenfeld said, who acknowledged the students had the option of looking for that at the end of the book. “And one of the words is ‘drag queen.’”

Kavanaugh, who often sits at the ideological center of the court, repeatedly came back to an argument that it wouldn’t be a huge problem for the district to simply allow parents to opt their children out.

“I’m not understanding why it’s not feasible,” he said.

But that argument has drawn sharp criticism from the schools and its allies. The schools said that an earlier effort to allow opt-outs was disruptive. And, they say, it would allow parents who object to any number of classroom discussions to opt out of a wide range of curriculum they find offense. What if, they argued, a student made a presentation in class about their same-sex parents: How could the teacher or principal be aware and handle notification of any possible presentation a parent might find objectionable?

“Once we say something like what you’re asking for us to say, it’ll be like opt-outs for everyone,” said liberal Justice Elena Kagan.

Leaning into religion

The school district told the court that the books are used like any other in the curriculum: Placed on shelves for students to find and available for teachers to incorporate into reading groups or read-alouds at their discretion. But the parents who object to the books said they are in active use. One challenge with the case is that it reached the Supreme Court before the record was fully developed in lower courts.

The Richmond-based 4th US Circuit Court of Appeals sided with the schools 2-1 last year, ruling that the record on how the books were being used was too scant at the early stage of litigation to determine whether the material burdened the religious rights of the parents.

The 6-3 conservative Supreme Court has sided with religious interests in every case it has considered in recent years – allowing a high school football coach to pray on the 50-yard line, permitting taxpayer money to be spent on religious schools and backing a Catholic foster care agency that refused to work with same-sex couples as potential parents.

The parents challenging the policy were represented by the religious legal organization Becket, which has brought several successful cases to the high court in recent years and has more pending.

In that sense, the Montgomery County schools were at a disadvantage before they even entered the courtroom on Tuesday. Kavanaugh seemed to flick at that point shortly before the arguments were over.

“Thank you,” Kavanaugh told Schoenfeld, sympathetically. “It’s a tough case to argue.”

This story has been updated following oral arguments.